14 van der Waals Interactions

So far we have considered electrostatic forces between charged and dipolar molecules. We have also introduced interactions which rely on the polarizability of molecules, either just the electronic polarizbility or also an orientational polarization of dipolar molecules.

A part of these interactions showed a specific distance dependence, which was \(r^{-6}\). In particular, we identified the Keesom interaction, i.e. the interaction of two freely rotating dipoles as well as the Debye interaction, i.e. the interaction of an induced dipole with a permanent dipole as two parts of the so-called van der Waals interaction.

Yet there also interaction between non-charged and non-polar molecules and this interaction is also belonging to this class and is specifically called dispersion interaction or London interaction.

As compared to other interactions, van der Waals interactions are typically

- long range

- attractive and orienting

- not additive

14.1 Dispersion Interaction

The dispersion part in particular, will require a quantum electrodynamic approach, which is beyond the scope of this lecture. We will will consider a much simpler approach at the beginning and later study the more general approach by McLachlan.

Consider first two atoms which have

- no time averaged dipole

- no residual charge

Depite this fact, the atoms may have an instantaneous dipole, which is causing and induced dipole in the other atom. Similarly, the second atom may cause a corresponding dipole in the first atom as well. This will effectively lead to an attractive interaction, which carries the spirit of the dispersion interaction. We can put that into a simple and very crude model based on the most basic semi-classical description of an atom.

This atom may consist of an electron and proton, which are separated by a distance \(a_0\), which corresponds to the Bohr radius. In this atom, the Coulomb interaction is given by

\[ E_\mathrm{pot}=\frac{e^2}{4\pi \epsilon_0 a_0} \]

This potential energy corresponds for an hydrogen atom to the ionization potential \(I=13.6\) eV. To ionize the atom, we can use electromagnetic radiation of the frequency \(\nu=3.3\times 10 ^{15}\) s\(^{-1}\). Thus, in principle a photon of energy \(h\nu=2.2\times 10^{-18}\) J would be sufficient to ionize the atom.

Accordingly, we have

\[h \nu= \frac{e^2}{4\pi \epsilon_0 a_0}\]

or we can write, that the Bohr radius of the electron orbit is given by

\[a_0=\frac{e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 h\nu}\].

In this simple classical picture the atom has an instantaneous dipole which corresponds to \(u=a_0 e\). This dipole creates a dipole field, that induces a dipole in the second atom. Using our previous findings for the dipole - induced dipole interaction yields

\[\begin{equation} w(r)=-\frac{u^2 \alpha_0}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6}=-\frac{(a_0 e)^2 \alpha_0}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6} \end{equation}\]

where \(\alpha_0\) is the electronic polarizability \(\alpha_0=4\pi \epsilon_0 a_0^3\). The latter gives

\[a_0^{2}=\frac{\alpha_0}{4\pi \epsilon_0 a_0}\]

from which we finally find the interaction energy

\[w(r)=-\frac{a_0^2 e^2 \alpha_0}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6}=-\frac{\alpha_0^2}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2}\frac{e^2}{4\pi \epsilon_0 a_0 }\frac{1}{r^6}\]

or

\[w(r)=-\frac{\alpha_0^2 h\nu}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6}\]

This simple semi-classical description corresponds to the result London (up to a factor of 3/4) obtained with a quantum-mechanical pertubation theory, which is

\[ w(r)=-\frac{C_\mathrm{disp}}{r^6}=-\frac{3}{4}\frac{\alpha_0^2 h\nu}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6}=-\frac{3}{4}\frac{\alpha_0^2I}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6} \]

So far, we assumed that both molecules have the same polarizability and thus are of the same type. If this is not the case, the interaction energy is given by

\[ w(r)=-\frac{3}{2}\frac{\alpha_{01},\alpha_{02}}{(4\pi \epsilon_0)^2 r^6}\frac{I_1 I_2}{I_1+I_2} \]

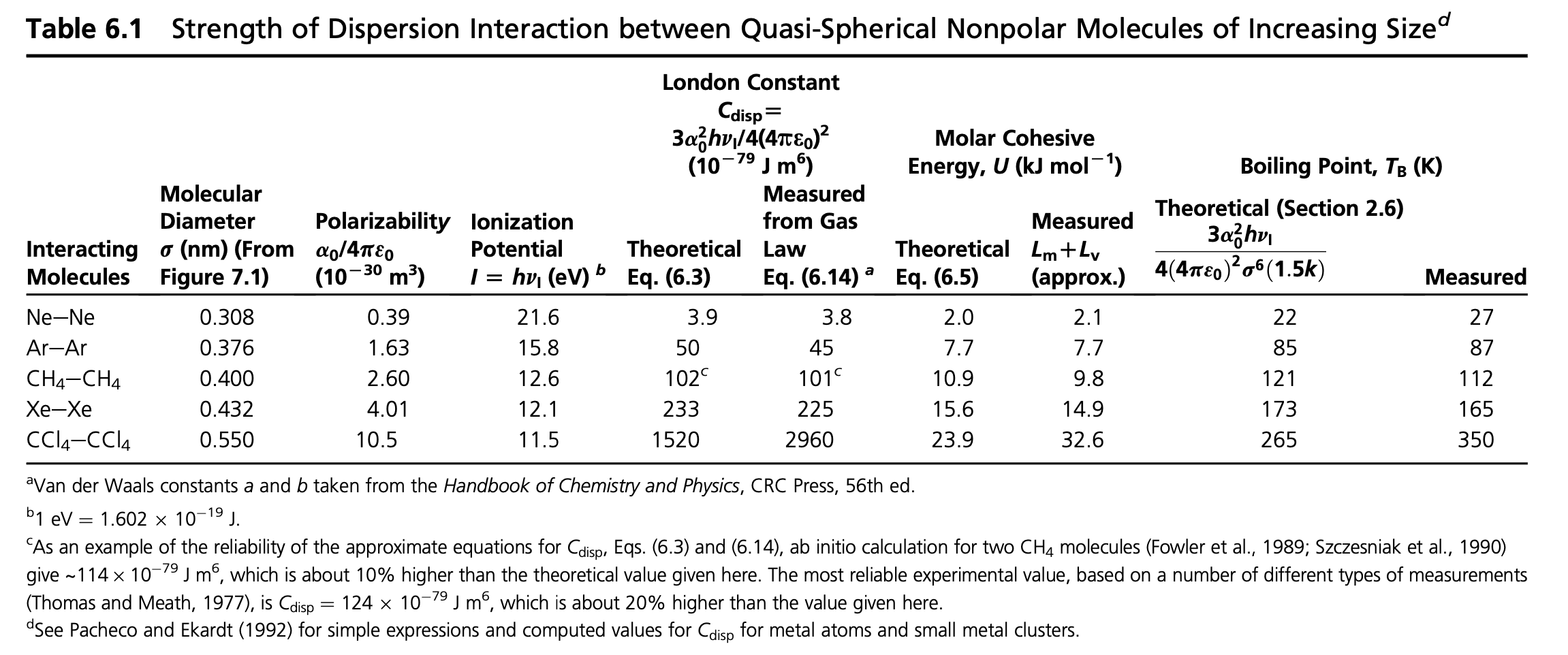

Example: Estimating the Boiling Point of Noble Gases

We can use this formula for the dispersion energy to estimate the boiling point of noble gases.

\[ w(r)+E_{\mathrm{kin}}=-\frac{3 \alpha_{0}^{2}}{4\left(4 \pi \epsilon_{0}\right)^{2} \sigma^{6}} h v_{\mathrm{I}}+\frac{3}{2} k_{\mathrm{B}} T_{\mathrm{m}}=0 \]

For Neon and Argon for example, we have the following parameters:

Ne: \(\sigma=3.08\) Angstroem, \(h\nu_I=21.6\) eV, \(\frac{\alpha_0}{4\pi \epsilon_0}=0.39\times 10^{-30}\) m\(^{-3}\), from which we obtain a boiling temperature of \(T_\mathrm{b}=22\) K, which nicely corresponds to the experimental value of \(T_\mathrm{b}=27\) K

Ar: \(\sigma=3.76\) Angstroem, \(h\nu_I=15.8\) eV, \(\frac{\alpha_0}{4\pi \epsilon_0}=1.63\times 10^{-30}\) m\(^{-3}\), from which we obtain a boiling temperature of \(T_\mathrm{b}=85\) K, which nicely corresponds to the experimental value of \(T_\mathrm{b}=87\) K

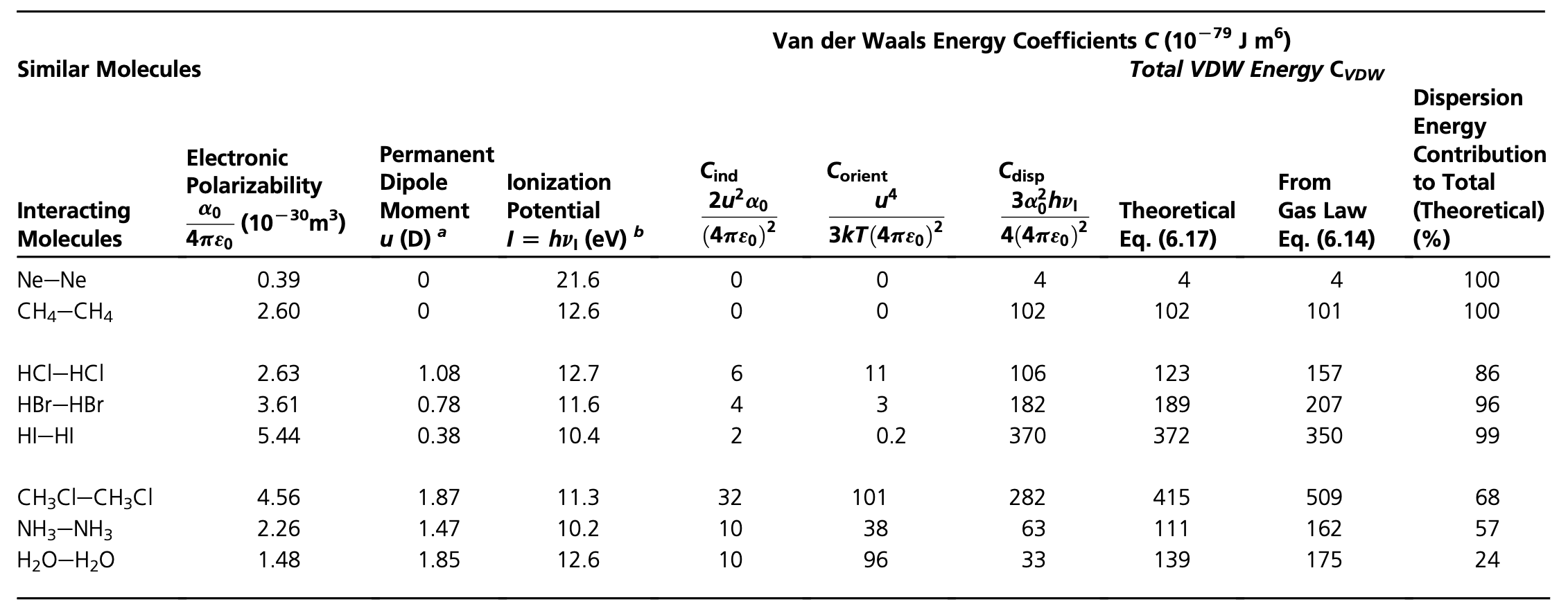

While the theory above provides us only with some idea about the dispersion interaction, we can now summarize all three contributions to the van der Waals interaction

\[ w_\mathrm{vdW}(r)=-\underbrace{\frac{u_{1}^{2} u_{2}^{2}}{3 k_{\mathrm{B}} T\left(4 \pi \epsilon_{0} \right)^{2} r^{6}}}_{\text{Keesom}}-\underbrace{\frac{u_{1}^{2} \alpha_{02}+u_{2}^{2} \alpha_{01}}{\left(4 \pi \epsilon_{0} \right)^{2} r^{6}}}_{\text {Debye }}-\underbrace{\frac{3 h\nu_1\nu_2 \alpha_{01} \alpha_{02}}{\left(4 \pi \epsilon_{0} \right)^{2} 2(\nu_1+\nu_2)r^{6}}}_{\text {London} } \]

or simply

\[ w_\mathrm{vdW}(r)=-\frac{C_\mathrm{vdW}}{r^6}=-\frac{C_\mathrm{Debye}+C_\mathrm{Keesom}+C_\mathrm{disp}}{r^6} \]

The individual contributions have different strength, but it is not difficult to see that the dispersion interaction is typically the biggest one as shown in the table below. The reason for that is the ionization potential and we will address this issue later in the section of the McLachlan theory.