Classes and Objects

Introduction to Object Oriented Programming

Imagine you’re simulating a complex physical system—perhaps a collection of interacting particles or cells. Each entity in your simulation has both properties (position, velocity, size) and behaviors (move, interact, divide). How do you organize this complexity in your code?

From Procedural to Object-Oriented Thinking

In previous lectures, we’ve designed programs using a procedural approach—organizing code around functions that operate on separate data structures. While this works for simpler problems, it can become unwieldy as systems grow more complex.

Object-oriented programming (OOP) offers a more intuitive paradigm: it combines data and functionality together into self-contained units called objects. Instead of having separate variables and functions, each object maintains its own state and defines its own behaviors.

For computational modeling, this is particularly powerful because:

- Objects can directly represent the entities you’re modeling (particles, cells, molecules)

- Code organization mirrors the structure of the real-world system

- Complex systems become easier to build incrementally and modify later

The Building Blocks: Classes and Objects

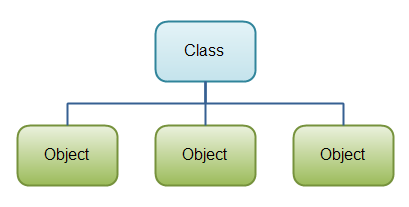

Object-oriented programming is built upon two fundamental concepts: classes and objects.

A class serves as a blueprint or template that defines a new type of object. Think of it as a mold that creates objects with specific characteristics and behaviors. It specifies:

- What data the object will store (properties)

- What operations the object can perform (methods)

An object is a specific instance of a class—a concrete realization of that blueprint. When you create an object, you’re essentially saying “make me a new thing based on this class design.”

Objects have two main components:

- Properties (also called attributes or fields): Variables that store data within the object

- Methods: Functions that define what the object can do and how it manipulates its data

Properties come in two varieties:

- Instance variables: Unique to each object instance (each object has its own copy)

- Class variables: Shared among all instances of the class (one copy for the entire class)

For example, if you had a Colloid class for a particle simulation:

- Instance variables might include

radiusandposition(unique to each particle) - Class variables might include

material_density(same for all colloids of that type) - Methods might include

move()orcalculate_volume()

Working with Classes in Python

Creating a Class

To define a class in Python, we use this basic syntax:

class ClassName:

# Class content goes hereThe definition starts with the class keyword, followed by the class name, and a colon. The class content is indented and contains all properties and methods of the class.

Let’s start with a minimal example that represents a colloidal particle:

Even this empty class is a valid class definition, though it doesn’t do anything useful yet. Let’s start adding functionality to make it more practical.

Creating Methods

Methods are functions that belong to a class. They define the behaviors and capabilities of your objects.

self in Python Classes

Every method in a Python class automatically receives a special first parameter, conventionally named self. This parameter represents the specific instance of the class that calls the method.

Key points about self: - It’s automatically passed by Python when you call a method - It gives the method access to the instance’s properties and other methods - By convention, we name it self (though technically you could use any valid name) - You don’t include it when calling the method

Example:

class Colloid:

def type(self): # self is automatically provided

print('I am a plastic colloid')

# Usage:

particle = Colloid()

particle.type() # Notice: no argument needed for selfIn this example, even though type() appears to take no arguments when called, Python automatically passes particle as the self parameter.

The Constructor Method: __init__

The __init__ method is a special method called when a new object is created. It lets you initialize the object’s properties with specific values.

Python also provides a __del__ method (destructor) that’s called when an object is deleted. This can be useful for cleanup operations or tracking object lifecycles.

String Representation: The __str__ Method

The __str__ method defines how an object should be represented as a string. It’s automatically called when: - You use print(object) - You convert the object to a string using str(object)

This method helps make your objects more readable and informative:

The .1f format specification means the radius will be displayed with one decimal place. This helps make your output more readable. You can customize this string representation to show whatever information about your object is most relevant.

Managing Data in Classes

Class Variables vs. Instance Variables

One of the core features of OOP is how it manages data. Python classes offer two distinct types of variables:

Instance Variables: Unique to Each Object

- Definition: Variables defined within methods, typically in

__init__ - Behavior: Each object has its own separate copy of these variables

- Usage: For properties that can vary between different instances

- Access pattern: Typically accessed as

self.variable_namewithin methods

Here’s a practical example showing both types of variables in action:

When to Use Each Type of Variable

Use Class Variables When:

- A property should be the same for all instances (like physical constants)

- You need to track information about the class as a whole (like counters)

- You want to save memory by not duplicating unchanging values

Use Instance Variables When:

- Objects need their own independent state

- Properties vary between instances (position, size, etc.)

- You’re representing unique characteristics of individual objects

Be careful when modifying class variables! Since they’re shared, changes will affect all instances of the class. This can lead to unexpected behavior if not managed carefully.