Coupled Differential Equations

In our previous lecture, we explored methods for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs) by examining the harmonic oscillator. We saw how a single differential equation can describe the motion of a simple physical system. However, most real-world systems involve multiple components that interact with each other, leading to coupled differential equations.

Coupled differential equations arise when the behavior of one variable directly influences another, and vice versa. These systems exhibit rich dynamics not possible in single-equation systems, including phenomena like synchronization, beats, and energy transfer. Understanding coupled systems is essential across physics, engineering, biology, and economics.

The coupled pendula system serves as an ideal introduction to coupled differential equations. It’s conceptually simple enough to visualize yet complex enough to demonstrate important physical phenomena. By connecting two pendula with a spring, we create a system where the motion of each pendulum affects the other, resulting in fascinating behaviors like normal modes and energy exchange.

In this lecture, we’ll formulate the coupled equations of motion, implement numerical solutions using SciPy’s advanced ODE solvers, visualize the results, and analyze specific cases like in-phase and out-of-phase motion. This will build directly on our previous work with single ODEs while introducing new concepts unique to coupled systems.

Coupled pendula

We will continue our course with some physical problems, we are going to tackle. One of the more extensive solutions will consider two coupled pendula. This belongs to the class of coupled oscillators, which are extremely important. They will later yield propagating waves. They are important for phonons, i.e. coupled vibration of atoms in solids, but there are also many other axamples. One can realize the coupled oscillation on different ways. He we will do that not with spring oscillators, by with pendula.

Description of the problem

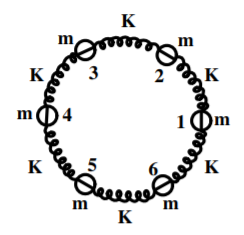

Sketch

The image below depicts the sitution we would like to cover in our first project. These are two pendula, which have the length \(L_{1}\) and \(L_{2}\). Both are coupled with a spring of spring constant \(k\), which is relaxed, when both pendula are at rest. You may want to include a generalized version where the spring is mounted at a distance \(c\) from the turning points of the pendula.

If you develop the equations of motion, write them down as a sum of torques. Use one equation of motion for each pendulum. The result will be two coupled differential equations for the angular coordinates. They are solved by the scipy solve_ivp function without any friction.

Equations of motion

The equations of motion of the two coupled pendula have the following form:

\[\begin{eqnarray} I_{1}\ddot{\theta_{1}}&=&-m_{1}gL_{1}\sin(\theta_{1})-kL_{1}^2[\sin(\theta_{1})-\sin(\theta_{2})]\\ I_{2}\ddot{\theta_{2}}&=&-m_{2}gL_{2}\sin(\theta_{2})+kL_{2}^2[\sin(\theta_{1})-\sin(\theta_{2})] \end{eqnarray}\]

These equations describe how the angular accelerations (\(\ddot{\theta}_{1}\) and \(\ddot{\theta}_{2}\)) of the two pendula depend on their positions and the coupling between them. Let’s break down each term:

\(I_{1}\ddot{\theta_{1}}\) and \(I_{2}\ddot{\theta_{2}}\) represent the angular acceleration multiplied by the moment of inertia for each pendulum. For a simple pendulum, the moment of inertia is given by \(I_1 = m_1L_1^2\) and \(I_2 = m_2L_2^2\), where \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) are the masses at the end of each pendulum, and \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) are the respective lengths of the pendula.

\(-m_{1}gL_{1}\sin(\theta_{1})\) and \(-m_{2}gL_{2}\sin(\theta_{2})\) are the gravitational torques acting on each pendulum. These terms would appear even if the pendula were not coupled, representing the natural restoring force that pulls each pendulum toward its equilibrium position.

\(-kL_{1}^2[\sin(\theta_{1})-\sin(\theta_{2})]\) and \(+kL_{2}^2[\sin(\theta_{1})-\sin(\theta_{2})]\) represent the coupling torques due to the spring connecting the pendula. The term \([\sin(\theta_{1})-\sin(\theta_{2})]\) approximates the horizontal displacement difference between the pendula, and these terms have opposite signs because the spring pulls the pendula toward each other. Now the spring pulls directly at the lengths \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) of the respective pendula rather than at a separate distance \(c\).

Here, \(\theta_{1}, \theta_{2}\) measure the angle of the two pendula with the length \(L_{1},L_{2}\). \(k\) is the spring constant of the spring coupling both pendula. The spring now connects directly at the end of each pendulum at distances \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) from their respective pivot points.

Solving the problem

Setting up the function

In our previous lecture, we used the solve_ivp function of scipy to solve the driven damped harmonic oscillator. Remember that we used the array

state[0] -> position

state[1] -> velocityto exchange position and velocity with the solver via the function that defines the physical problem

def SHO(time, state):

g0 = state[1] ->velocity

g1 = -k/m * state [0] ->acceleration

return np.array([g0, g1])for a coupled system of different equations, we can now extend the state array. In the case of the coupled system of equations it has the following structure

def SHO(time, state):

g0 = how the velocity of object 1 depends on the velocities of all objects

g1 = how the acceleration of object 1 depends on the positions and velocities of all objects

g2 = how the velocity of object 2 depends on the velocities of all objects

g3 = how the acceleration of object 2 depends on the positions and velocities of all objects

return np.array([g0, g1, g2, g3])So the state vector just gets longer and the coupling is in the definition of the velocities and accelerations. The results are then the positions and velocities of the objects. Use this type of scheme to define the problem and write a function, which returns the state of the objects as before.

Define initial parameters

We want to define some parameters of the pendula

- length of the pendulum 1, \(L_1\)=3

- length of the pendulum 2, \(L_2\)=3

- gravitational acceleration, \(g=9.81\)

- mass at the end of the pendula, \(m=1\)

- distance where the coupling spring is mounted, \(c=2\)

- spring constant of the coupling spring, \(k=5\)

As compared to our previous problem of a damped driven pendulum, where we had two initial conditions for the second order differential equation, we have now two second order differential equation. We therefore need 4 initial parameters, which are the initial elongations of both pendula and their corresponding initial angular velocities We will notice, that the solution,i.e. the motion of the pendula, will strongly depend on the initial conditions.

Solve the equation of motion

We have to define a timeperiod over which we would like to obtain the solution. We use here a period of 400s where we calculate the solution at 10000 points along the 400s.

We are now ready to calculate the solution. Finally, we extract also the angles of the individual pendula, their angular velocities and the position of the point masses at the end of the pendulum. This can be then readily used to create some animation.

Plotting

First, get some impression of how the angles change over time.

Normal Modes

We will not cover all the physical details here, but you might remember your mechanis lectures, that two coupled oscillators show distinct modes of motion, which we would call the normal modes. Four two coupled pendula there are two normal modes, where both pendula move with the same frequency. We may force the system into one of its normal modes, by specifying its initial conditions properly.

In-phase motion

The first one, will create an in-phase motion of the two pendula by setting their initial elongation equal, i.e. \(\theta_{1}(t=0)=\theta_{2}(t=0)\). Both pendula then oscillate with their natural frequency and the coupling spring is never elongated.

Out-of-phase motion

The second one, will create a motion in which the two pendula are out-of-phase by a phase angle of \(\pi\) , i.e. \(\theta_{1}(t=0)=-\theta_{2}(t=0)\). Both pendula then oscillate with a frequency higher than their natural frequency. This is due to the fact that there is a higher restoring force due to the action of the spring.

Beat case

The last case is not a normal mode but represents a more general case. We start with two different initial angles, i.e. \(\theta_{1}(t=0)=\pi/12\) and \(\theta_{2}(t=0)=0\). This is the so-called beat case, where the pendula exchange energy. The oscillation, which is at the beginning in only in the first pendulum is then transfer to the second one. This transfer of energy is continuously occurring from one pendulum to the other since there’s nowhere for the energy to go. From this point it’s easily to recognize how the wife is generated. In a set of many coupled pendula one pendulum is starting to oscillate and is transferring it’s energy to the next one and then to the next one and then to the next one and this way the energy is propagating along all oscillators.

Computation of energy (here for the beat case)

After we have had a look at the motion of the individual pendula, we may also check, the energies in the system. We have to calculate the potential and kinetic energies of the pendula and we should not forget the potential energy stored in the spring.

Potential energy of the pendula

The potential energy plot below nicely shows the exchange of energy between the two pendula in the beat case.

Potential energy of the spring

Kinetic energies

Total energy

As the total energy in the system shall nbe conserved, the sum of all energy contributions should yield a flat line.

Total energy exchange of the pendula

While the plot above Shows the total energy of both pendula we may now have a look at the total energy in each pendulum. The plots clearly show that the energy is exchanged between the two pendula. The residual ripples on the curve results from the fact that we here exclude the potential energy stored in the spring.

Summary and Key Concepts

In this lecture, we’ve explored coupled pendula as a quintessential example of coupled differential equations. Through this physical system, we’ve uncovered several fundamental concepts in physics and differential equations:

Coupled Differential Equations: We’ve seen how interactions between two pendula lead to a system of coupled ODEs where the motion of each pendulum affects the other.

Normal Modes: We discovered that coupled systems possess characteristic oscillation patterns called normal modes (in-phase and out-of-phase), where the system behaves like a single harmonic oscillator.

Beat Phenomenon: When initial conditions excite both normal modes simultaneously, we observed beats—a periodic exchange of energy between the pendula resulting in amplitude modulation.

Energy Transfer: We analyzed how energy flows between the pendula through the coupling spring, highlighting conservation of total energy while individual pendulum energies vary.

Numerical Solutions: We implemented solutions using

solve_ivpwith the Runge-Kutta method, demonstrating how modern computational techniques can handle complex coupled systems.

These concepts extend far beyond pendula, appearing in diverse applications:

- Molecular vibrations in chemistry and materials science

- Coupled oscillators in electronic circuits

- Normal modes in structural engineering

- Resonance phenomena in mechanical systems

- Wave propagation in coupled systems

This concept of normal modes is critical for understanding more complex molecular systems. Below are visualizations of normal modes in two molecular structures:

Self-Exercise

Try changing the coupling constant k to see how it affects the motion of the pendula. Use the “beat case” initial conditions (one pendulum displaced, the other at rest) and observe what happens.

- Start with our current value (k = 0.5)

- Try a smaller value (k = 0.1)

- Try a larger value (k = 2.0)

What differences do you observe in how quickly energy transfers between the pendula?

The energy transfer between pendula happens faster with stronger coupling (larger k) and slower with weaker coupling (smaller k).