Optical Instruments

The Human Eye

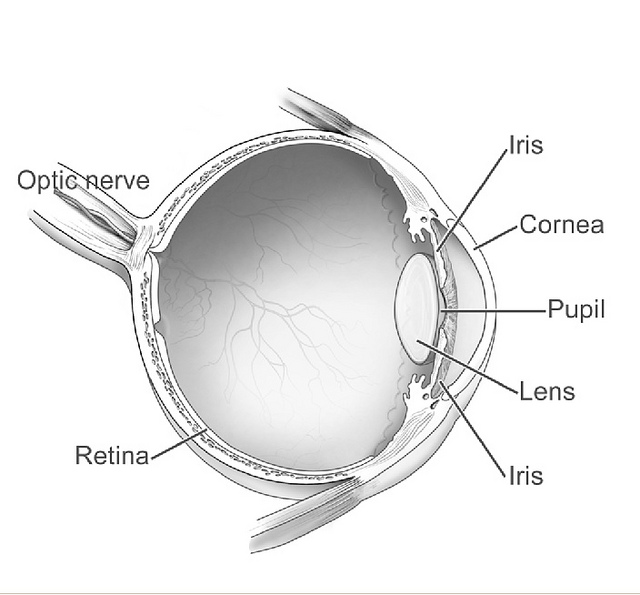

The human eye stands is one of the most remarkable sensory systems. This sophisticated organ combines an array of precisely crafted components—including an adjustable aperture, an adaptive lens, and a highly sensitive photodetector—all interconnected with a neural network capable of rapid and accurate pattern recognition. What’s truly astounding is that this entire system operates on mere watts of power.

Key Components and Their Functions

Pupil and Iris: The pupil, surrounded by the iris, acts as an adjustable aperture. It regulates the amount of light entering the eye and influences the depth of field. In bright conditions, a constricted pupil increases the depth of field, allowing a wider range of distances to be in focus simultaneously.

Lens: Connected to the ciliary muscles, the lens can change its curvature to adjust focal length, a process known as accommodation. This allows the eye to focus on objects at varying distances.

Vitreous Humor: This gel-like substance fills the eye cavity, maintaining its shape and contributing to the eye’s optical properties.

Retina: The light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye, containing photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) that convert light into neural signals.

Photoreceptors: Cones and Rods

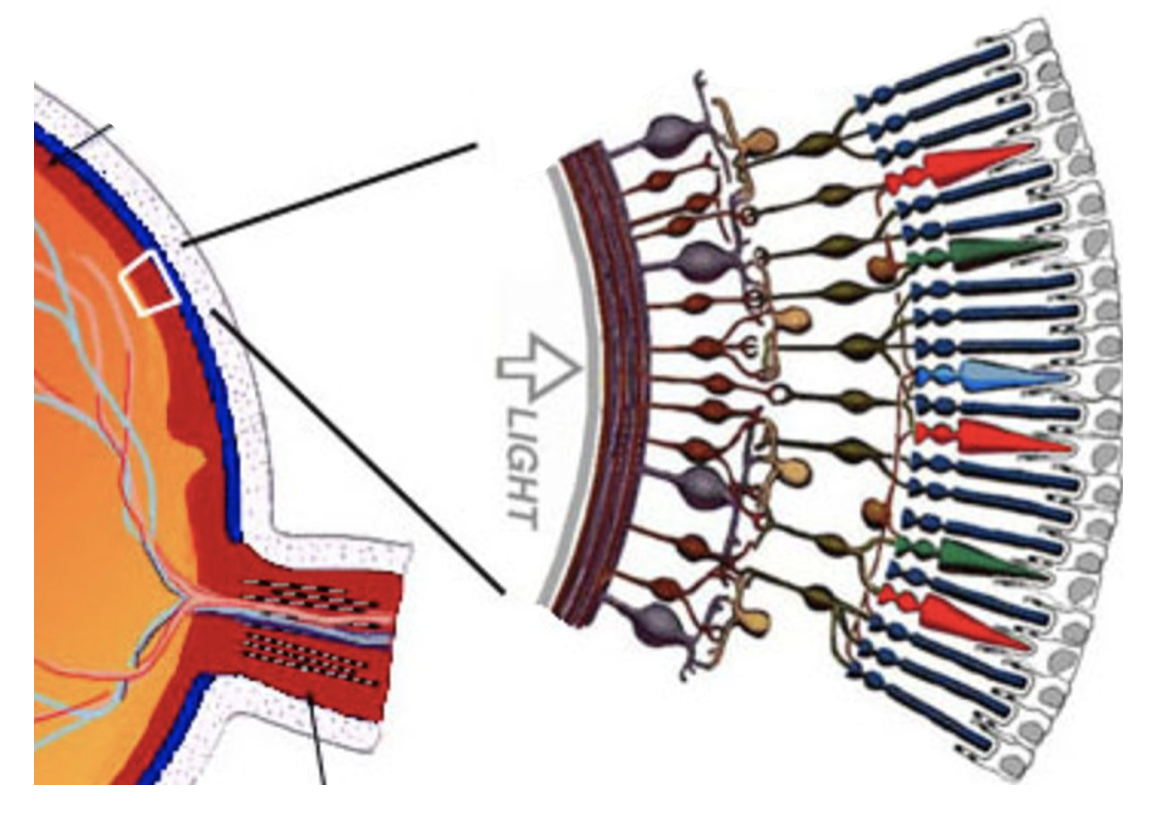

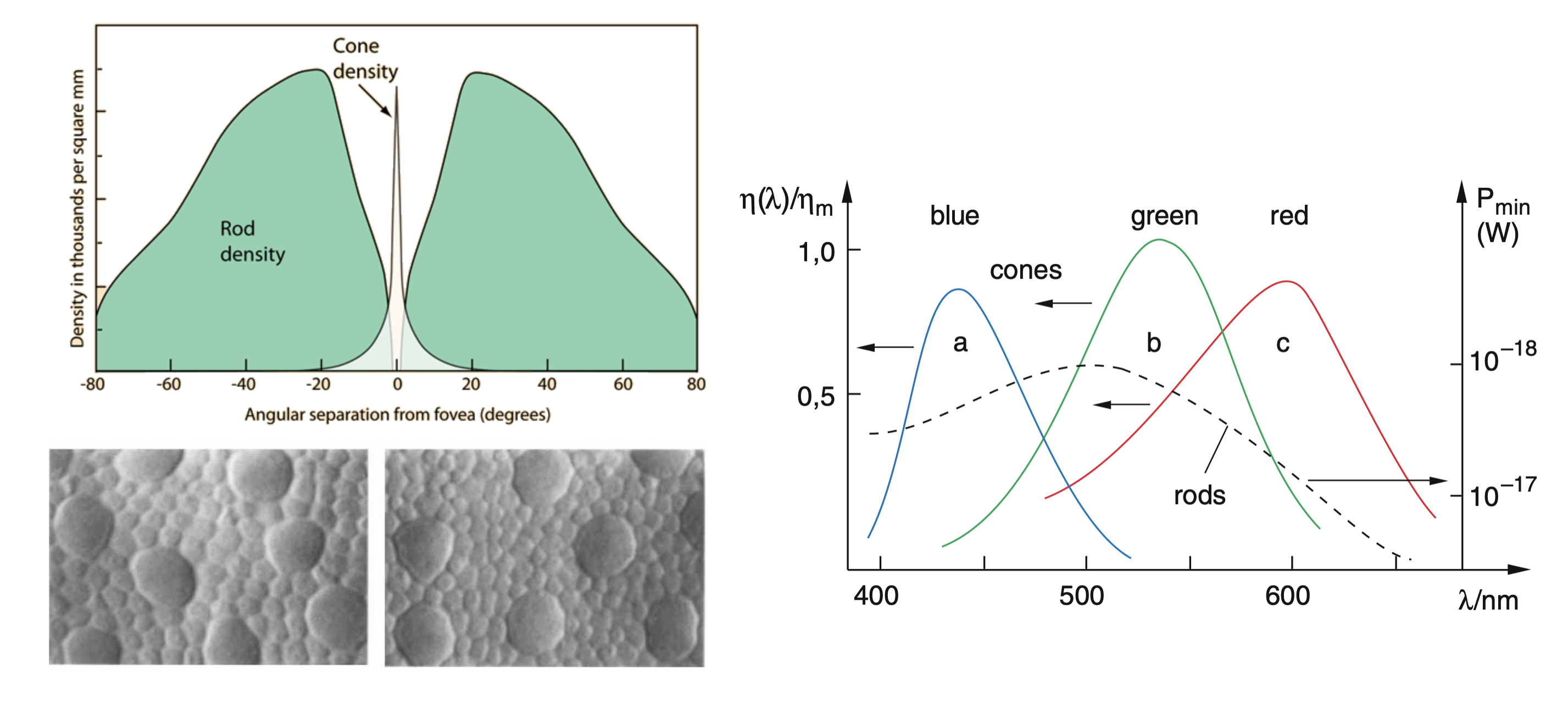

The retina contains two types of photoreceptor cells:

Cones: Responsible for color vision and high acuity in bright light. They are concentrated around the fovea, the area of highest visual acuity. There are about 6 Million cones in the human eye.

Rods: More sensitive to light but do not distinguish colors, providing vision in low light conditions. There are around 12 Million rods in the human eye.

Rods and cones obtain their function from a chromophore molecule called retina, which undergoes a conformational change when exposed to light. This change triggers a cascade of chemical reactions that ultimately lead to the generation of neural signals. The color vision is achieved with the same chromophore molecule that is embedded in slightly different protein structures in cones. This allows cones to be sensitive to different wavelengths of light.

Cones contain light-sensitive pigments based on retinal molecules, which undergo conformational changes when excited by light, triggering a cascade of chemical processes. There are three types of cones, each sensitive to different wavelengths of light, enabling color vision.

Visual Acuity and Performance

Visual acuity, often measured using an eye chart, quantifies the eye’s ability to resolve fine details. It’s typically expressed as a fraction (e.g., 20/20 vision), where the numerator is the test distance and the denominator is the distance at which a person with normal acuity can read the same line.

The human eye’s remarkable performance in pattern recognition, depth perception, and adaptability to varying light conditions is achieved through the complex interplay of its optical components and neural processing. This sophisticated system continues to inspire developments in artificial vision systems and optical technologies.

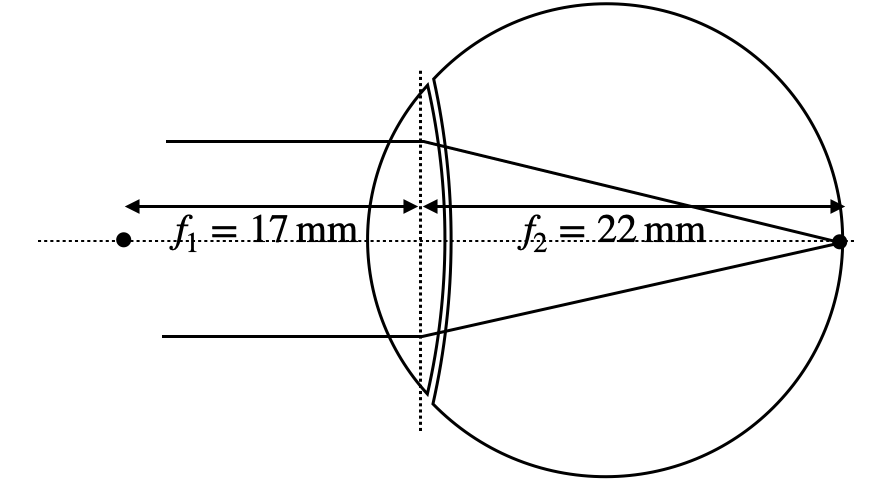

Optical Properties of the Eye

The eye’s optical system is asymmetrical due to the different media it interfaces with (air on one side, vitreous humor on the other). This results in different focal lengths:

- Front focal length:

- Back focal length:

These values can change during accommodation for near vision:

- Close object front focal length:

- Close object back focal length:

The eye’s refractive power, measured in diopters (D), is the reciprocal of the focal length in meters. For a relaxed eye:

During accommodation, this can increase to about 52 D.

Resolution Limit of the Eye

The resolution of the eye is limited by diffraction and the spacing of photoreceptors. The minimum angle of resolution θ_min can be approximated by:

where λ is the wavelength of light and D is the diameter of the pupil. For a 3 mm pupil and 555 nm light (peak sensitivity), this gives a theoretical resolution of about 1 arc minute.

Refractive Errors and Visual Correction

The human eye, under normal conditions, focuses images of distant objects onto the retina at the back focal distance of approximately 22 mm. However, various refractive errors can occur due to imperfections in the eye’s optical system, primarily the cornea and lens. These errors affect the eye’s ability to focus light accurately on the retina, leading to vision problems.

Common refractive errors include:

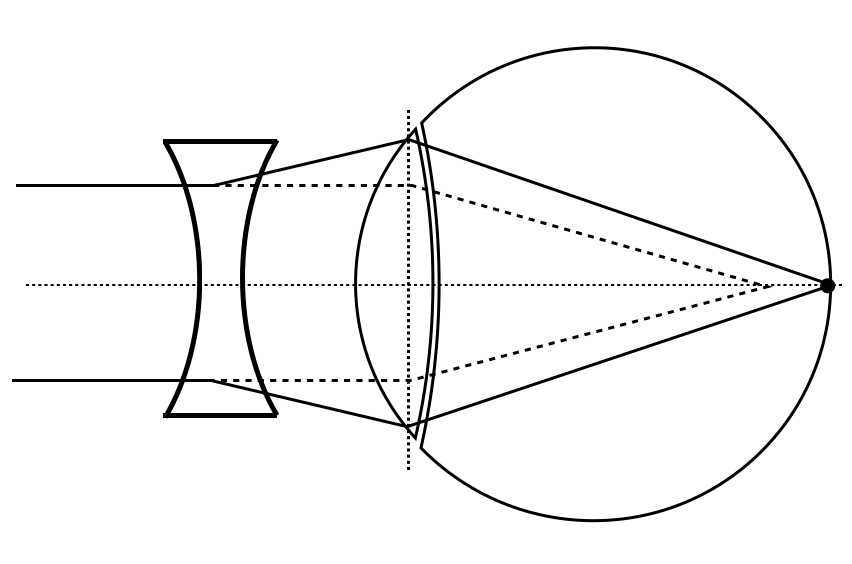

Myopia (Short-sightedness): Light from distant objects focuses in front of the retina, causing distant objects to appear blurry while near objects remain clear.

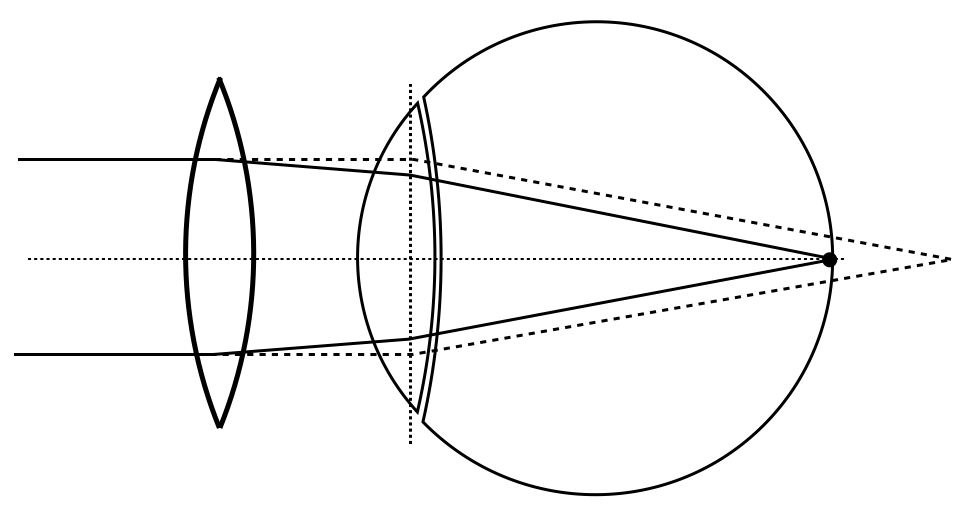

Hyperopia (Far-sightedness): Light focuses behind the retina, making nearby objects appear blurry while distant objects may remain clear.

Astigmatism: The cornea or lens isn’t perfectly spherical, causing light to focus at multiple points rather than a single sharp point on the retina.

The severity of refractive errors can be quantified using the concept of refractive power. The refractive error R of the eye, measured in diopters (D), is calculated as:

where f_required is the focal length needed for perfect focus, and f_actual is the eye’s actual focal length. This formula helps determine the degree of correction needed for various eye defects.

In a normal, relaxed state, the human eye can observe objects clearly up to a distance of approximately

This relationship is fundamental in understanding how objects are perceived and in designing corrective lenses and optical instruments.

history |grep git

Understanding these concepts is crucial for diagnosing vision problems and designing appropriate corrective measures, whether through eyeglasses, contact lenses, or surgical interventions.

Magnification

Having discussed the basic structure and function of the human eye, we now turn to how optical instruments can enhance our vision. Instead of calculating the magnification of optical instruments from object and image distances, we introduce a more relevant measure: the angular magnification.

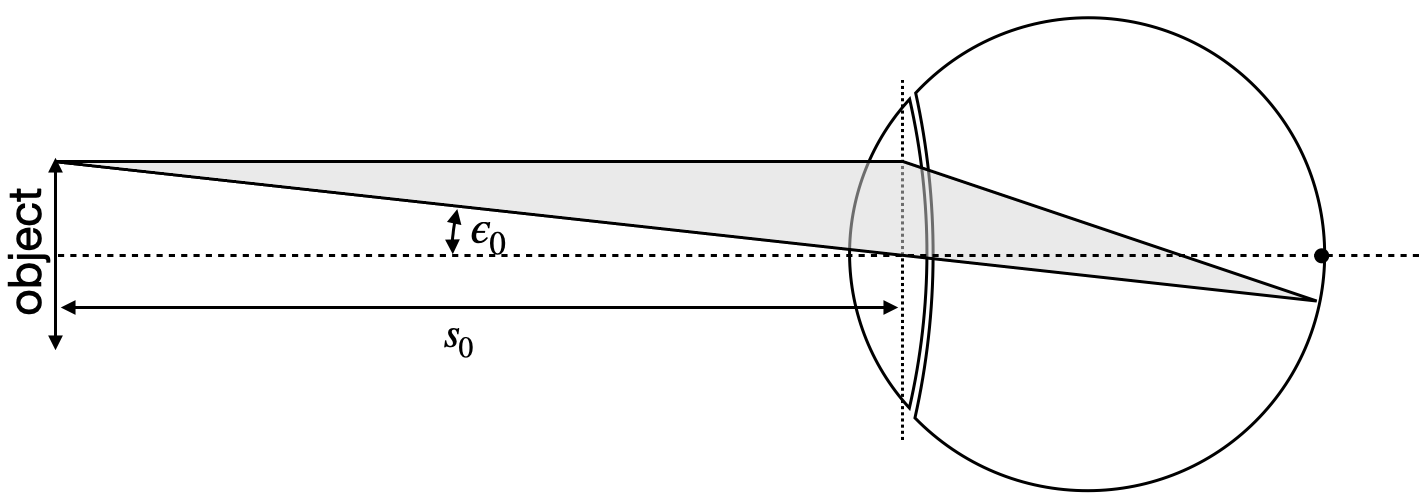

The angular magnification, V, is defined as the ratio of the angle subtended by the image when viewed through the instrument to the angle subtended by the object when viewed with the naked eye at the near point. It is given by:

where: - ε is the angle subtended by the image at the eye when viewed through the instrument - ε₀ is the angle subtended by the object when viewed with the naked eye at the near point

This concept is crucial in understanding how optical instruments like telescopes and microscopes enhance our vision. Angular magnification effectively increases the apparent size of objects by increasing the angle at which they are viewed. This measure is particularly useful as the actual image size is often not directly accessible or relevant to the viewer’s experience.