Optical Instruments

Microscope

Optical Microscopy has a rich history of development, and is a very important tool in the fields of biology, materials science, and nanotechnology. Here are some key milestones in the history of microscopy:

Ancient Times - 13th Century: Simple magnifying glasses - The concept of magnification was known to ancient civilizations. - In the 13th century, Italian craftsmen created the first wearable glasses.

1590: Compound Microscope - Hans and Zacharias Janssen, Dutch spectacle makers, created the first compound microscope.

1665: Robert Hooke’s “Micrographia” - Hooke published detailed observations made with his improved compound microscope. - He coined the term “cell” after observing cork tissue.

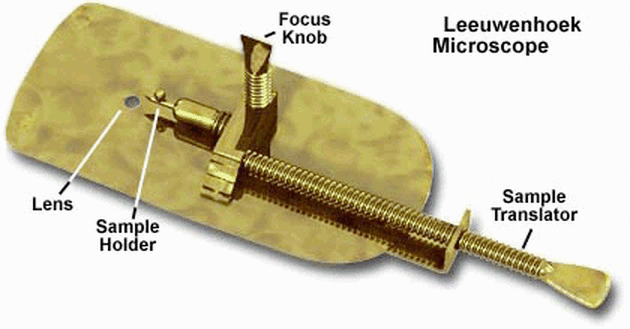

1670s: Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s Single-Lens Microscopes - Developed high-quality single-lens microscopes with up to 270x magnification. - First to observe and describe bacteria, yeast, and other microorganisms.

18th-19th Centuries: Achromatic Lenses - Joseph Jackson Lister developed achromatic lenses, reducing chromatic aberration.

1830s: Ernst Abbe’s Theoretical Work - Formulated the Abbe Sine Condition, crucial for modern lens design.

Late 19th Century: Oil Immersion Lenses - Allowed for higher resolution in light microscopy.

1931: Electron Microscope - Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll developed the first electron microscope.

1950s-1960s: Phase Contrast and Fluorescence Microscopy - Frits Zernike invented phase contrast microscopy. - Development of fluorescence microscopy techniques.

1981: Scanning Tunneling Microscope - Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer invented the STM, allowing imaging at the atomic level.

1980s-Present: Digital and Computational Microscopy - Integration of CCD cameras and digital imaging. - Development of confocal microscopy, super-resolution techniques, and computational methods like ptychography.

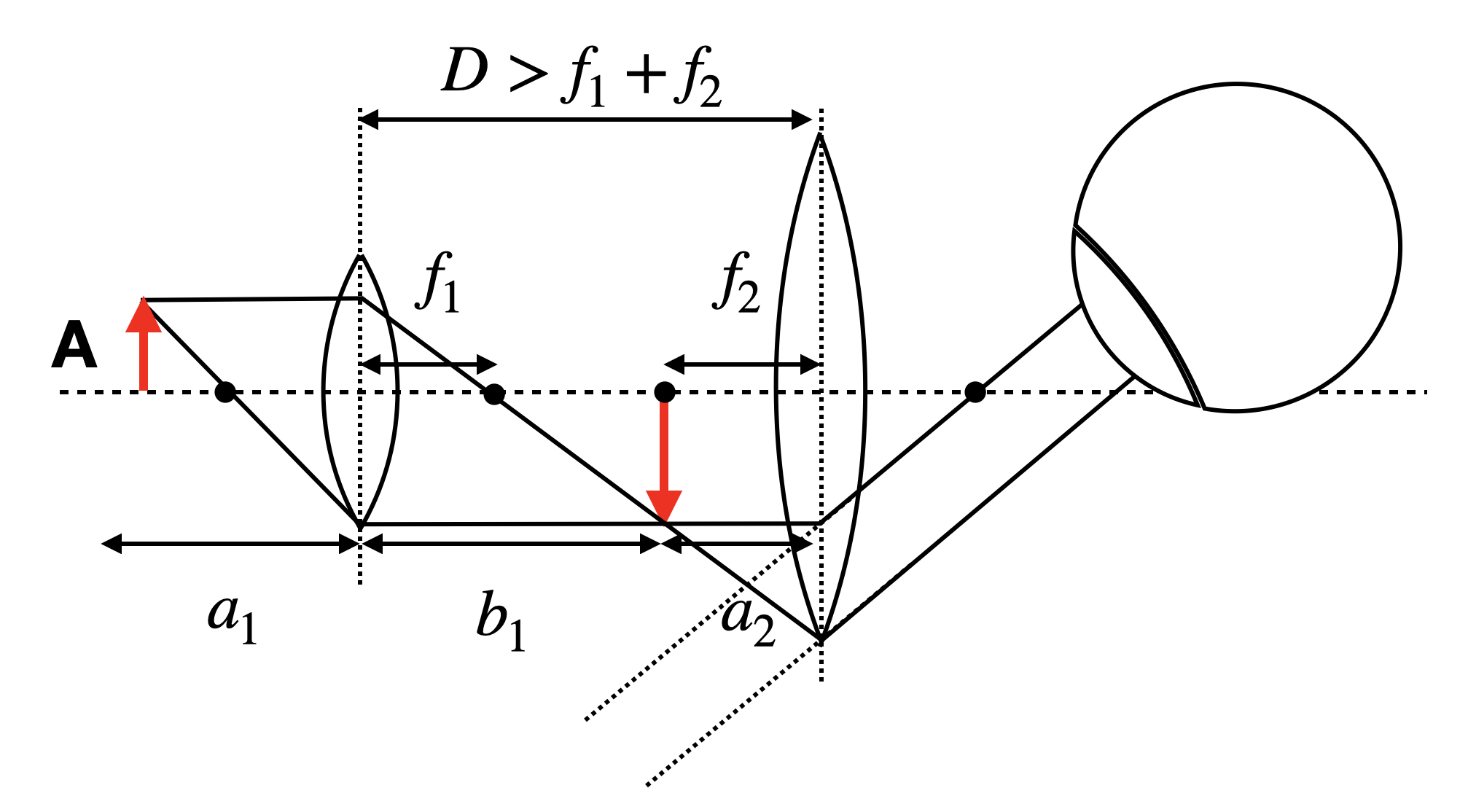

In this section we will analyze the optical properties of microscopes from the perspective of geometrical optics which explains image formation. Yet, the key to the performance of a microscope is the understanding provided by wave optics. We will discuss this in a later section. The simplest form of a microscope consists of an objective lens with a focal distance

the object is placed at a distance

For this simple microscope system we may calculate first the intermediate image position

resulting in

If we assume a

The intermediate image of size

If we observe the object of a size

and we may obtain the total angular magnification

If we set the distance between the two lenses to

which says that the magnification is the result of the two focal length

Modern microscopy

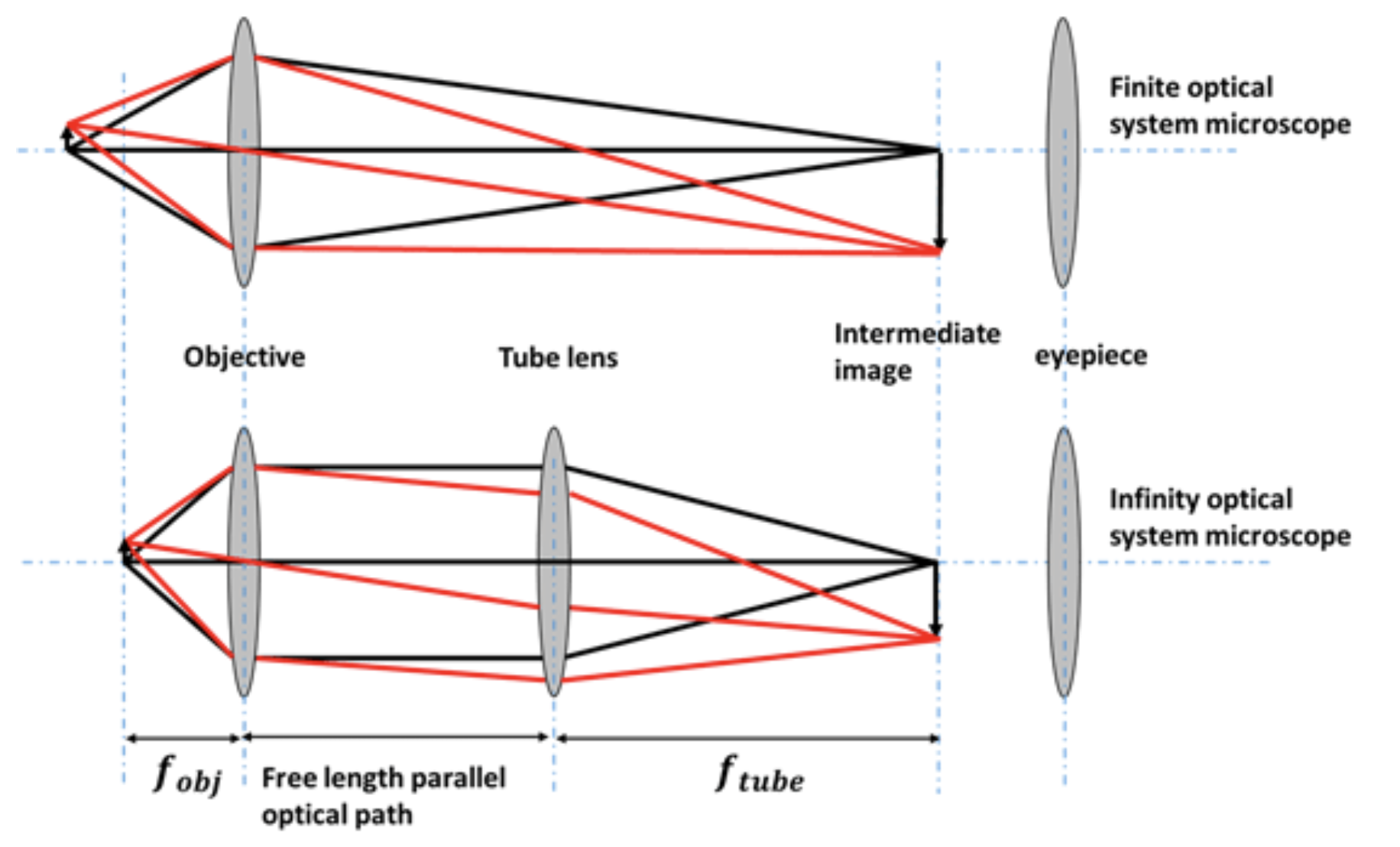

While the description above accurately represents the simplest microscope design, contemporary microscopes employ more intricate light paths and generally utilize what is known as infinity corrected optics. This system incorporates an objective lens that projects images of objects in the focal plane to infinity. Such an objective lens is invariably paired with a secondary lens, called the tube lens. Together, these lenses are engineered to provide a magnification level that is specified on the objective lens housing.

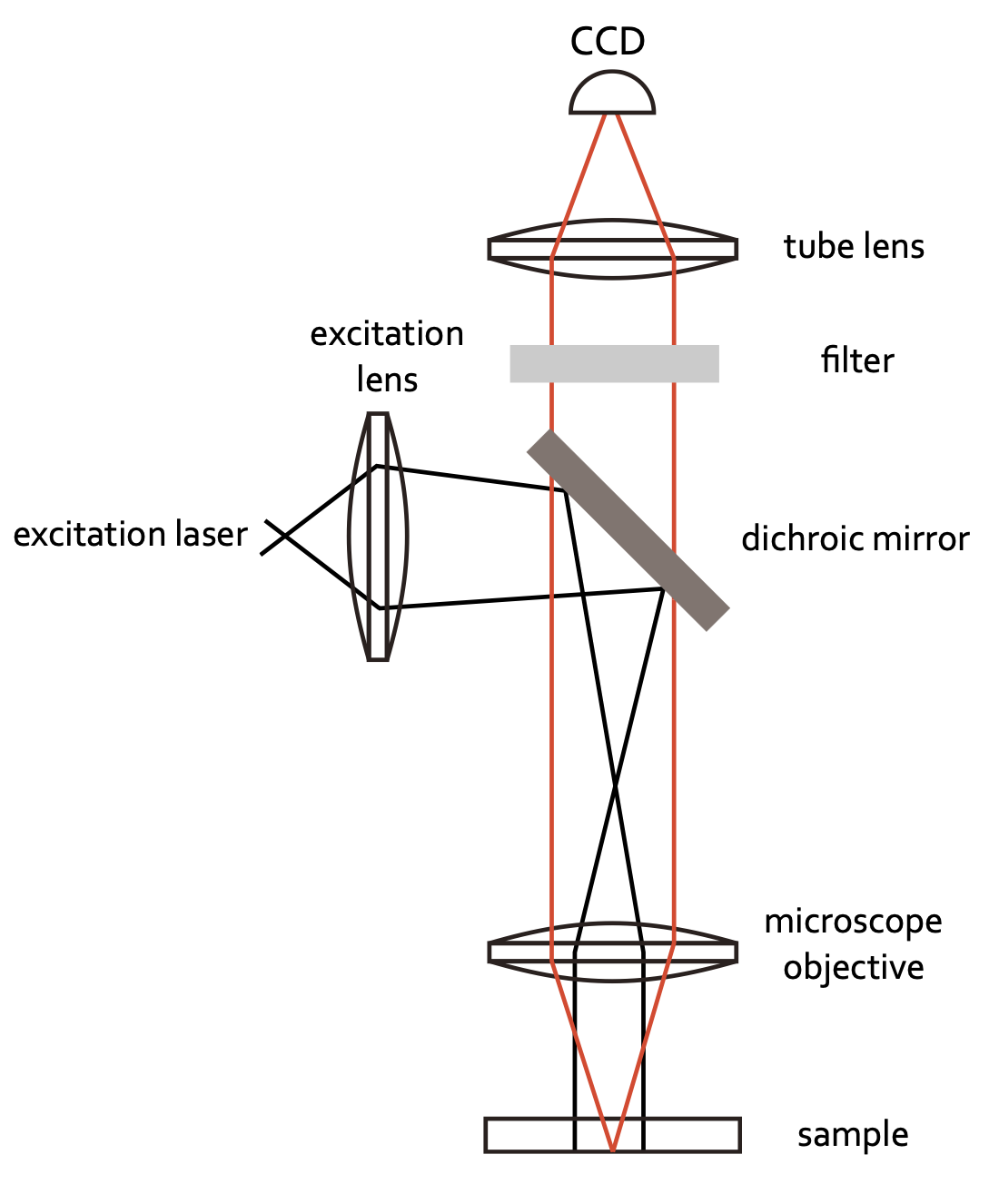

Infinity optics allows you to have a free length with a parallel optical path where you can insert optical elements. There is no fixed tube length as in the case sketched above, where the distance of the intermediate image has to be considered. Therefore, it has tremendous technical advantages. Common optical microscopes are further today coupled to CCD cameras to record images digitally. Yet, an eye-piece may still be available in many cases. The sketch below shows the light path for a simple fluorescence microscope recording fluorescence images with a camera.

Digital Microscopy

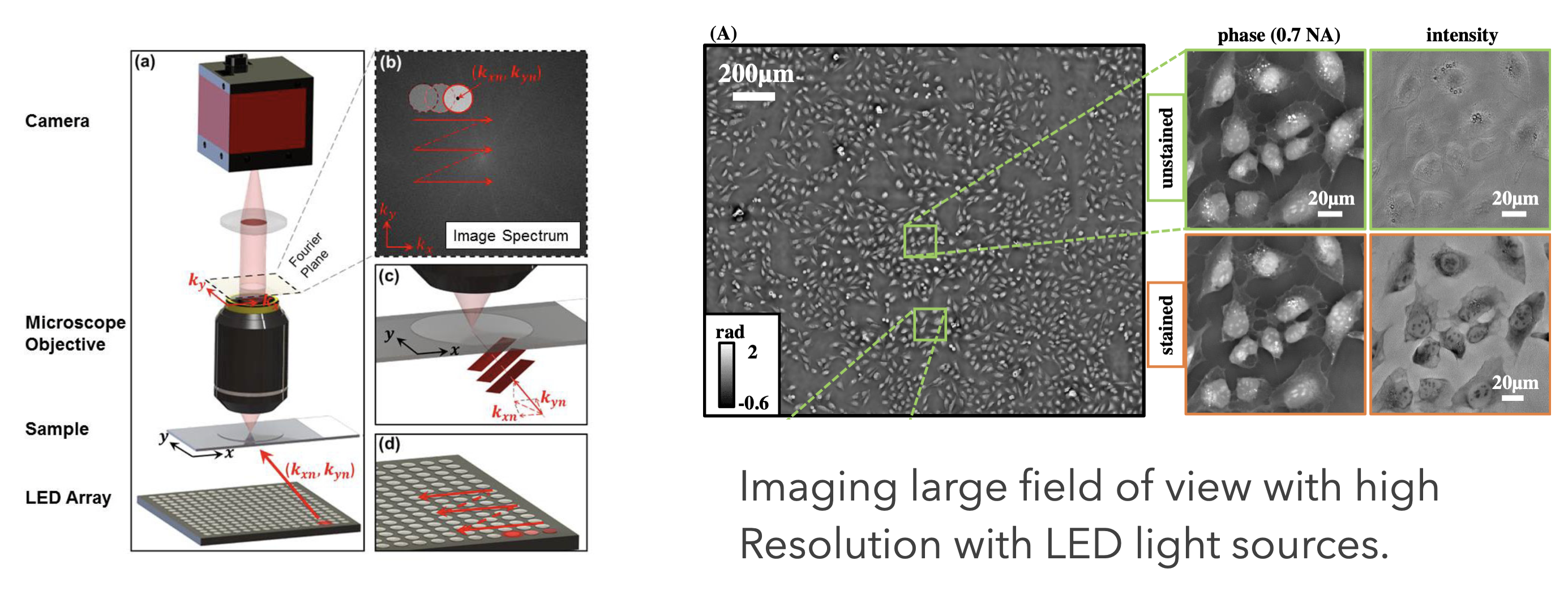

The possibility to digitally record images creates endless possibilities to computationally enhance and combine images. Nowadays the field of optics is one of the fastest developing fields in physics with numerous new techniques appearing every week. In this field of imaging methods of machine learning also play an increasingly important role. While I’m not ablields in physics with numerous new techniques appearing every week. In this field of imaging methods of machine learning also play an increasingly important role. While I am not able to refer to all possible optical microscopy techniques he to refer to all possible optical microscopy techniques here, I will exemplarily show some data from the Waller group at Berkley using computational methods to enhance the resolution by keeping at the same time a large field of view for imaging. This technique is called ptychography and can be understood if you consider Fourier Optics (a field of optics describing ligh propagation in terms Fourier transforms).

There is a massive amount of other techniques with increadible images being generated. Have a look around.

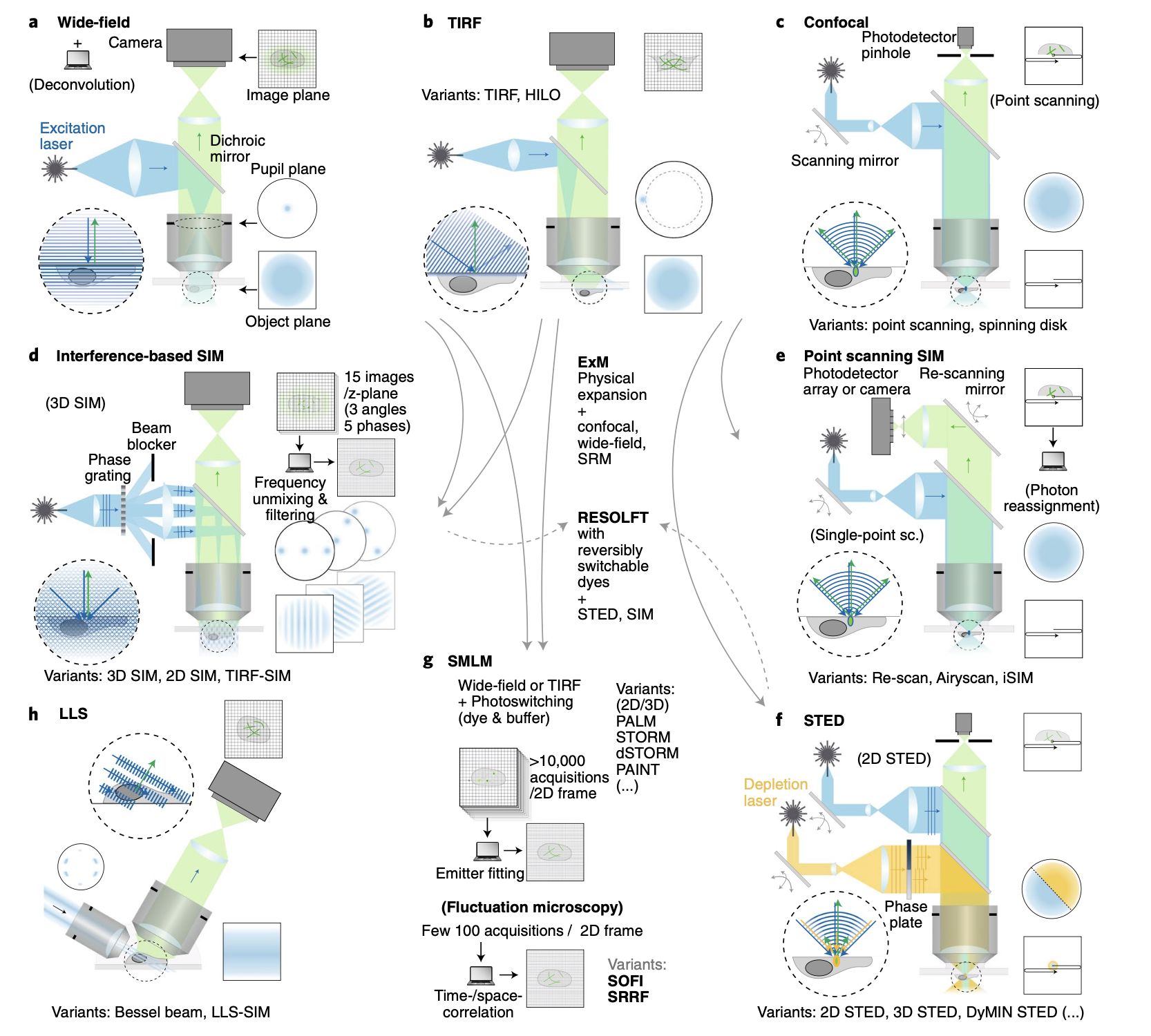

While traditional light microscopy has been invaluable, it’s limited by the diffraction of light, restricting resolution to about 200 nm as will be discussed in a later part of this course. Modern techniques have pushed beyond this limit, revolutionizing our ability to visualize microscopic structures.

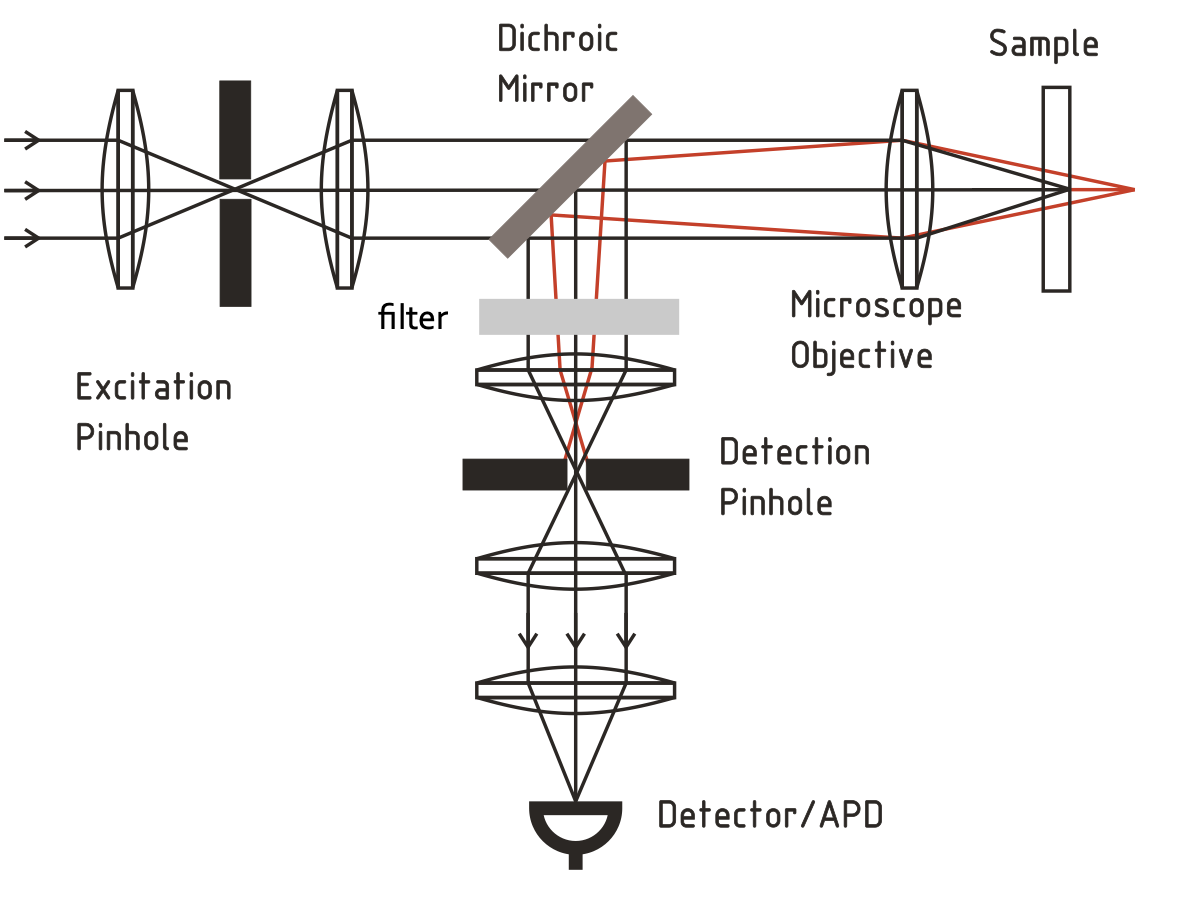

Confocal Microscopy

Confocal microscopy uses point illumination and a pinhole in an optically conjugate plane in front of the detector to eliminate out-of-focus signal.

- Key Features:

- Improved optical resolution and contrast

- Ability to collect serial optical sections from thick specimens

- Widely used in biological sciences

- Overcoming Limitations:

- Eliminates background information away from the focal plane

- Allows for 3D reconstruction of samples

Examples for Super-Resolution Microscopy Techniques

Super-resolution techniques bypass the diffraction limit, achieving resolutions down to tens of nanometers.

- Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) Microscopy

- Uses two laser beams: one to excite fluorescent molecules, another to suppress fluorescence around the excitation spot

- Overcoming Limitations: Achieves resolution as fine as 20-50 nm by precisely controlling which fluorophores are allowed to fluoresce

- Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (PALM)

- Relies on selective activation and sampling of sparse subsets of photoactivatable fluorescent molecules

- Overcoming Limitations: Locates individual molecules with nanometer precision by isolating their signals over time

- Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM)

- Similar to PALM, but uses photoswitchable fluorophores

- Overcoming Limitations: Achieves resolutions of ~20 nm by precisely locating the centers of single fluorescent molecules

- Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM)

- Uses patterned illumination to create moiré fringes, which are computationally processed to reconstruct super-resolution images

- Overcoming Limitations: Doubles the resolution of traditional light microscopy to ~100 nm

- Superresolution Photothermal Infrared Imaging

- Superresolution photothermal infrared imaging is a novel technique that brings the advantages of superresolution microscopy to the infrared regime.

- Overcoming Limitations: Achieves resolutions of ~300 nm for infrared imaging at wavelength of 10 µm by using photothermal lensing effects.