The resolution of an optical microscope is fundamentally limited by the diffraction of light as it passes through the optical components, particularly the objective lens. Diffraction causes point sources of light to produce blurred images rather than perfect points, affecting the microscope’s ability to distinguish between two closely spaced objects.

Rayleigh’s Criterion for Resolution

Key Question: How close can two point sources be while still being perceived as distinct entities by an optical system?

To answer this, we need to consider two essential aspects of how a lens modifies light:

Wavefront Transformation: A lens alters the curvature of incoming wavefronts, focusing parallel rays (plane waves) to a point in the focal plane.

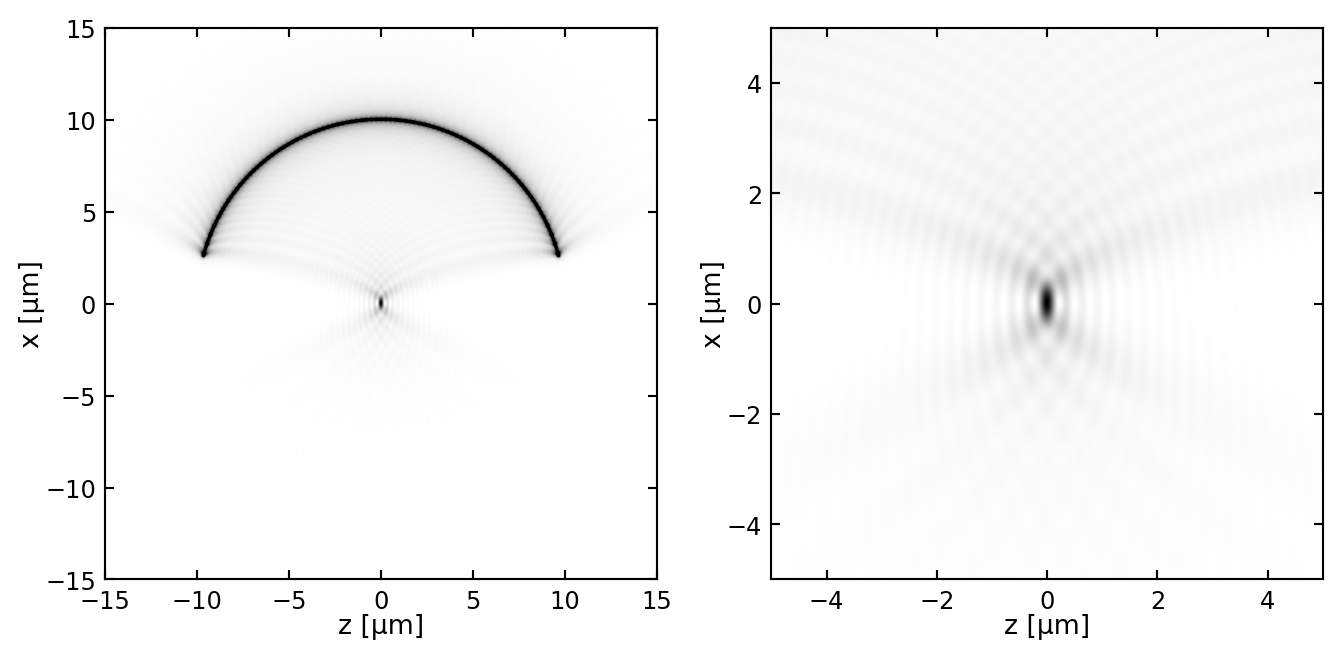

Finite Aperture Effects: The lens has a finite size and acts as a circular aperture, introducing diffraction effects that spread the image of a point source into a diffraction pattern known as the Airy disk.

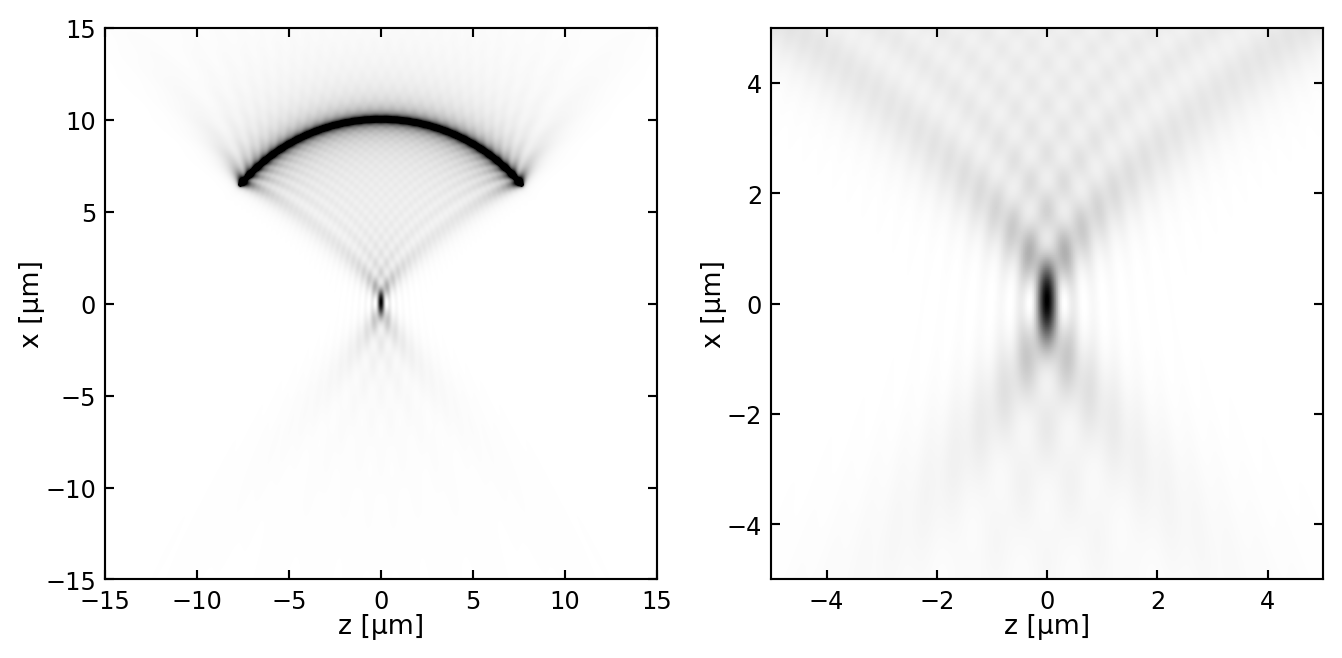

Visual Representation:

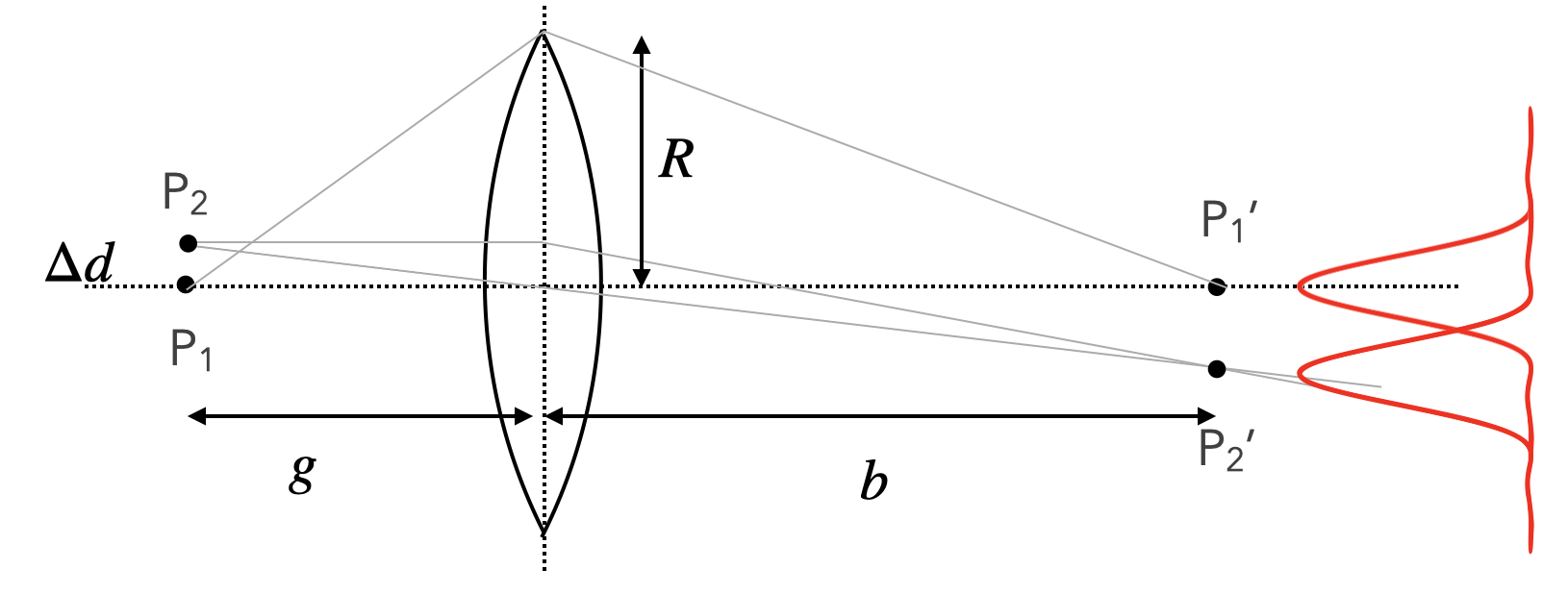

Each point source produces its own diffraction pattern. As the sources move closer, their patterns begin to overlap, making it harder to distinguish between them.

Rayleigh’s Resolution Criterion:

- Two point sources are considered just resolvable when the principal maximum (center) of one Airy pattern coincides with the first minimum (dark ring) of the other.

For incoherent light sources (where the light waves are not in phase), this criterion corresponds to a 26% dip in intensity between the two peaks, which is generally sufficient for the human eye or detectors to distinguish the two sources as separate.

Angle to the First Minimum:

The angle to the first minimum of the diffraction pattern from a circular aperture of radius is given by:

Since the diameter of the aperture , this can also be written as:

The factor 1.22 arises from the first zero of the Bessel function that describes the diffraction pattern of a circular aperture.

Small Angle Approximation:

For small angles (common in optical systems), in radians.

Relating Angular to Linear Separation in the Image Plane:

The angular resolution corresponds to a linear separation in the image plane (at image distance ):

Combining the Equations:

Substituting :

Solving for :

Considering the Object Plane:

The magnification of the optical system is:

where is the object distance. The corresponding separation in the object plane () is:

Substituting :

Introducing Numerical Aperture (NA):

The numerical aperture (NA) of the lens is defined as:

where:

- is the refractive index of the medium between the object and the lens.

- is the half-angle of the maximum cone of light that can enter or exit the lens.

Since , we have:

Substituting into :

Therefore, incorporating the refractive index :

Under Rayleigh’s resolution criterion, several key factors influence the resolving power of an optical system.

Firstly, a higher numerical aperture (NA) improves resolution. This increase can be achieved by enhancing either the refractive index of the medium between the object and the lens or the sine of the collection angle . Since the NA is defined as , a larger NA allows the lens to gather more diffracted light, thereby resolving finer details in the image. In air, where the refractive index is approximately , the maximum achievable NA is less than 1, which limits the resolution. This limitation arises because the maximum value of is 1 (when ), so the NA in air cannot exceed 1. In practical systems, the collection angle is much less than , further reducing the NA and thus the resolution. Immersion lenses, which use a medium with a higher refractive index (such as water or oil), can achieve higher NAs, overcoming this limitation and improving resolution.

Secondly, using shorter wavelengths of light leads to better resolution. According to the formula , the minimum resolvable distance is directly proportional to the wavelength. Therefore, decreasing the wavelength reduces , allowing the optical system to distinguish smaller features of the object.

Rayleigh’s Resolution Criterion

Two incoherent point sources can be resolved when their minimum separation satisfies:

Where:

- is the minimum resolvable distance between the two point sources.

- is the wavelength of the light used for imaging.

- is the numerical aperture of the optical system.

- is the refractive index of the medium.

- is the half-angle of the maximum cone of light entering the lens.

Abbe’s Criterion for Resolution

Limitations of Rayleigh’s Criterion:

- Rayleigh’s criterion applies to incoherent light sources, where the intensities of the diffraction patterns add directly.

- It does not fully account for the effects of coherence and interference in the imaging process.

Ernst Abbe developed a theory that considers the imaging of coherent light sources, where the phases of the waves are correlated. It emphasizes the importance of diffracted orders and spatial frequencies in the formation of images.

The key concepts in Abbe’s theory are

Diffraction Grating Analogy:

- An object with fine details can be thought of as a diffraction grating that scatters light into multiple diffraction orders.

- The ability to resolve these fine details depends on the optical system’s capacity to capture these diffracted orders.

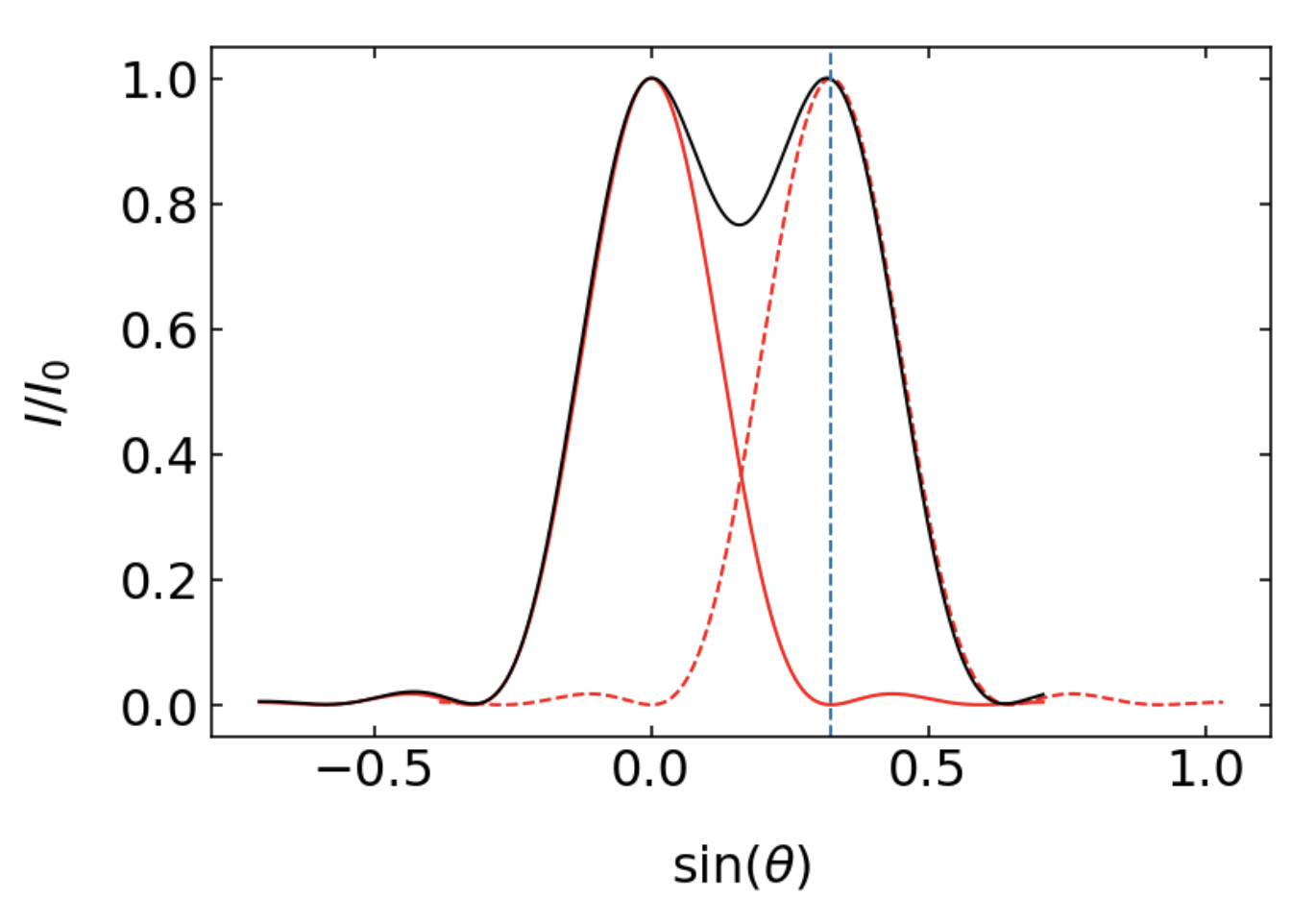

Spatial Frequencies:

- The finer the details in the object, the higher the spatial frequency.

- High spatial frequencies correspond to larger angles in the diffraction pattern.

Optical Transfer Function:

- Describes how different spatial frequencies are transmitted through the optical system.

- An optical system with a larger NA can transmit higher spatial frequencies, improving resolution.

Following that analogy, Abbe’s criterion states that the minimum resolvable distance between two points in the object plane is given by:

Abbe’s Limit:

- Emphasizes coherent imaging and the transmission of at least two diffracted orders (zeroth and first) for resolution.

Rayleigh’s Limit:

- Based on the visibility of intensity dips in the overlapping Airy patterns of incoherent sources.

Implications in Microscopy:

Coherent Illumination:

- Techniques like phase-contrast or interference microscopy rely on coherent light.

- Abbe’s criterion is more appropriate for these methods.

Incoherent Illumination:

- Common in conventional bright-field microscopy.

- Rayleigh’s criterion provides a practical resolution limit.

Importance of Abbe’s Criterion:

- Highlights the role of interference between diffracted waves in image formation.

- Demonstrates that resolution is fundamentally limited by the wavelength of light and the NA of the system.

- Suggests that capturing higher spatial frequencies (larger NA) leads to better resolution.