Reflection

The study of reflection has a rich history dating back to ancient times:

Ancient Greece (300 BCE): Euclid, in his work “Catoptrics,” was among the first to formally describe the law of reflection. He stated that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection.

Ancient Rome (50 CE): Hero of Alexandria expanded on Euclid’s work, applying the principle that light travels along the path of least distance.

Islamic Golden Age (1000 CE): Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) made significant contributions to optics in his “Book of Optics.” He conducted experiments to verify the law of reflection and explored the properties of spherical and parabolic mirrors.

17th Century: Fermat’s Principle, formulated by Pierre de Fermat, provided a more general framework for understanding reflection (and refraction) based on the principle of least time.

Modern Era: The understanding of reflection has been further refined with the development of electromagnetic theory by James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century and quantum optics in the 20th century.

The law of reflection is probably the most simple one. Yet the simplicity gives us the chance to define some basic objects which we will further use for the description of light rays and their propagation.

Law of Reflection

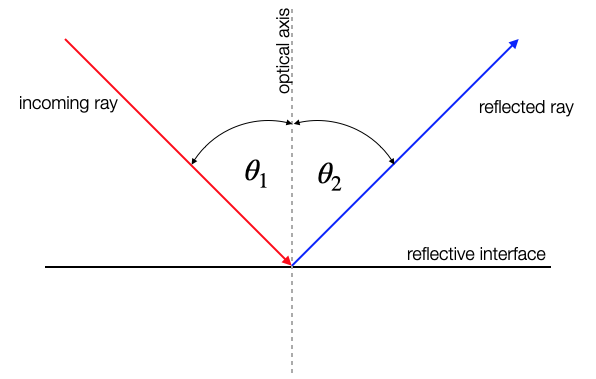

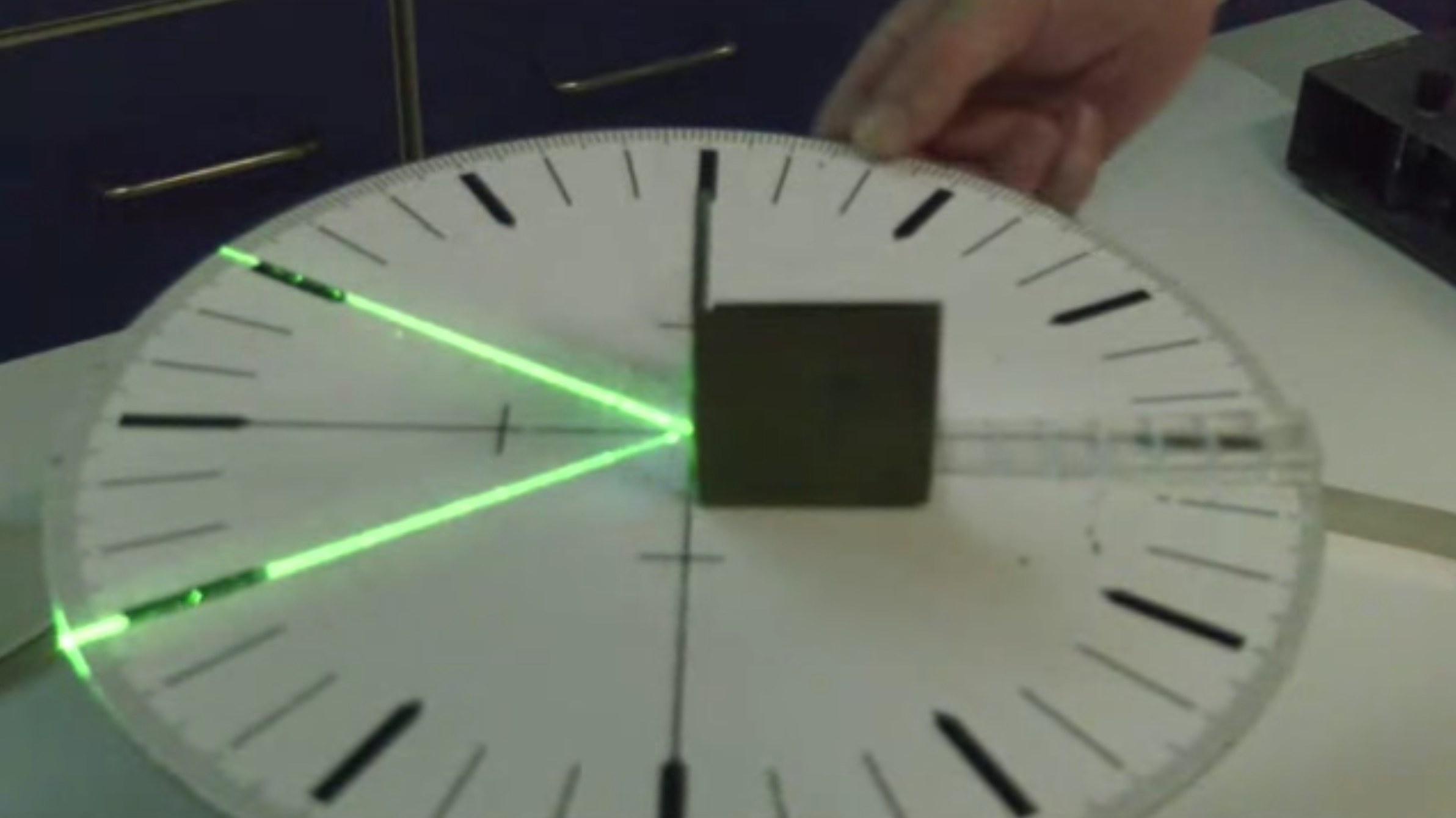

The sketch below shows the reflection of an incoming light ray (red) on an interface. This incoming light ray has an angle

Figure 1 (a) shows the reflection of an incoming light ray (red) on an interface. This incoming light ray has an angle

The law of reflection tells us now, that the outgoing reflected ray is now leaving the surface under an angle

If a ray is incident to a reflecting surface under an angle

Fermat’s Principle

The law of reflection can be actually obtained from a variational principle saying the light rays propagate along those path on which the propagation time is an extremum. This variational principle is called Fermat’s principle.

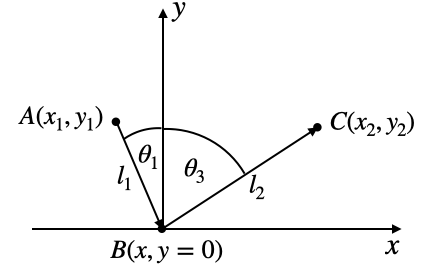

Consider now a light ray that should travel from point

The path taken by a ray between two given points A, B is the path that can be traversed in the least time.

More precise alternative: A ray going in a certain particular path has the property that if we make a small change in the ray in any manner whatever, say in the location at which it comes to the mirror, or the shape of the curve, or anything, there will be no first-order change in the time; there will be only a second-order change in the time.

So let us consider that contraints to the path length. The total length the light hast to travel via the three points is

The time that is required by the light to travel that distance

where

This results in Eq. 1

which is actually

or

which finally requires

and is our law of reflection. Thus, reflection satisfies Fermat’s principle, i.e. the light rays propagate along those path on which the propagation time is an extremum.

The Principle of Least Action, also known as Hamilton’s Principle, is a fundamental concept in classical mechanics. It states that the path taken by a physical system between two states is the one for which the action integral is stationary (usually a minimum).

Action Integral

The action

Lagrangian

The Lagrangian

where:

Euler-Lagrange Equations

Hamilton’s Principle leads to the Euler-Lagrange equations, which are the equations of motion for the system. These equations are derived by requiring that the action

This condition leads to the following differential equations:

These are the Euler-Lagrange equations, and they provide a powerful method for deriving the equations of motion for a wide variety of physical systems.

Example: Simple Harmonic Oscillator

For a simple harmonic oscillator with mass

Applying the Euler-Lagrange equation:

we get:

which is the familiar equation of motion for a simple harmonic oscillator.

Hamilton’s Principle and the associated Euler-Lagrange equations are foundational in classical mechanics and have far-reaching implications in other areas of physics, including quantum mechanics and field theory.