This page was generated from `/home/lectures/exp3/source/notebooks/L1/Refraction.ipynb`_.

Refraction¶

The law of refraction is the second important law of geometrical optics. It connects the refractive index

Refractive Index¶

The refractive index

Snells Law¶

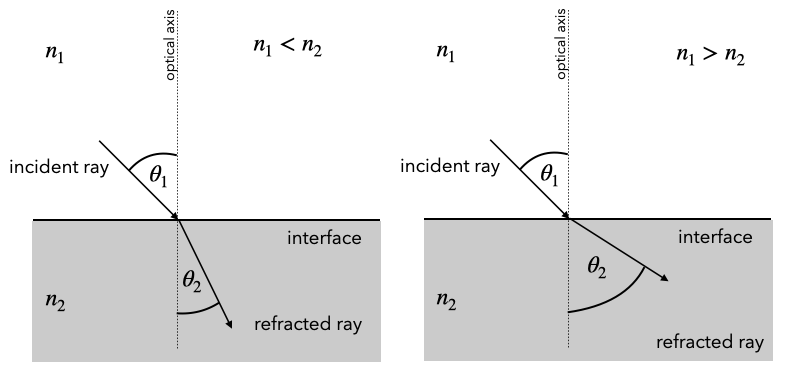

|

|---|

Fig.: Snell’s law. |

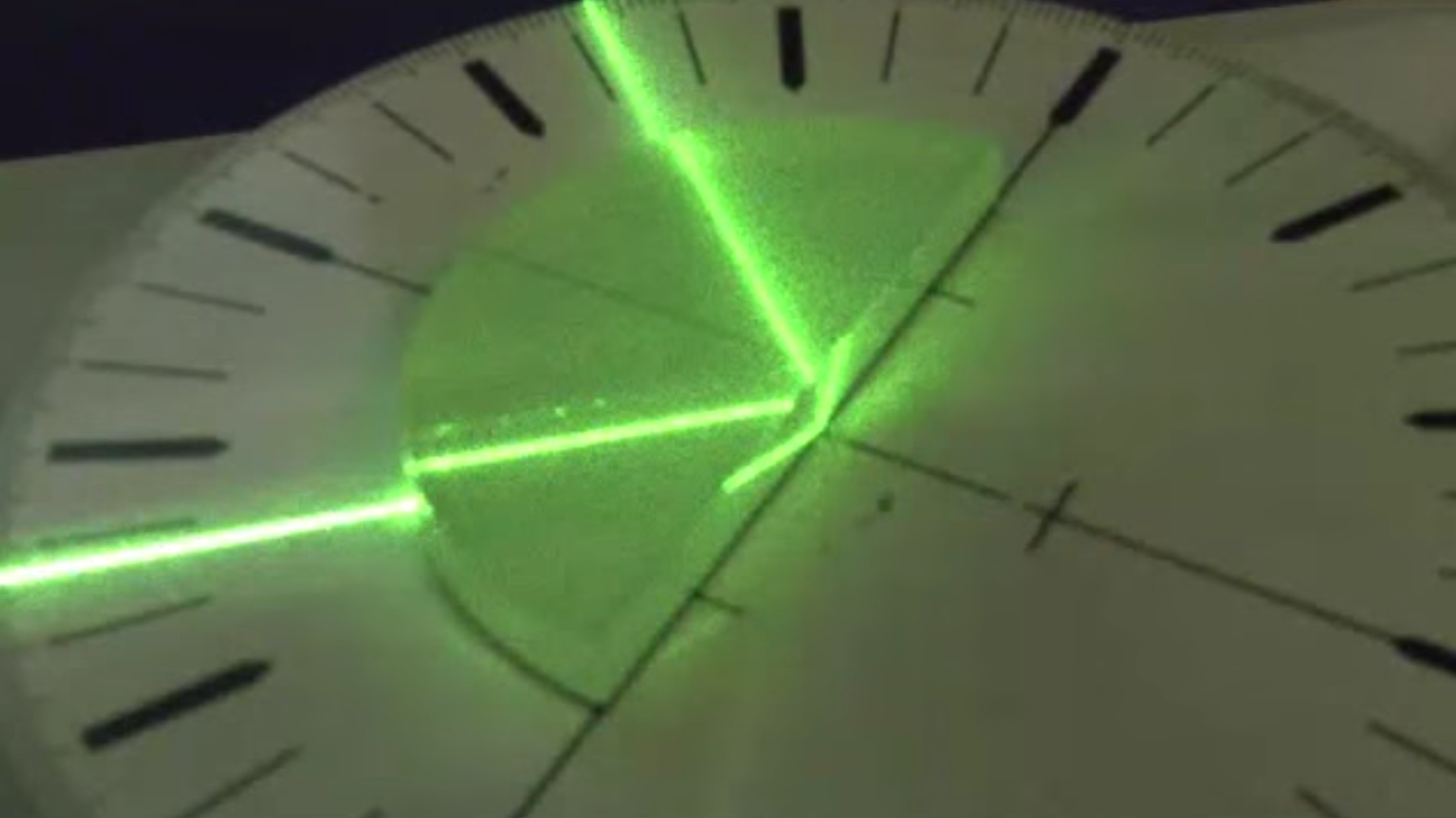

Law of Reflection (Snells Law)

The law of refraction (Snell’s law) is given for the above sketch by

In the previous section in refraction we have derived the law of reflection from Fermat’s principle. Try yourself to obtain Snell’s law with the help of Fermat’s principle. Check out the Refraction Explorer Snippet if you want to play around with Snells law. You may tray there even negative refraction.

According to Snell’s law, there is a general behavior of the corresponding angles, which you might want to remember (see also Fig. above). Consider the following cases:

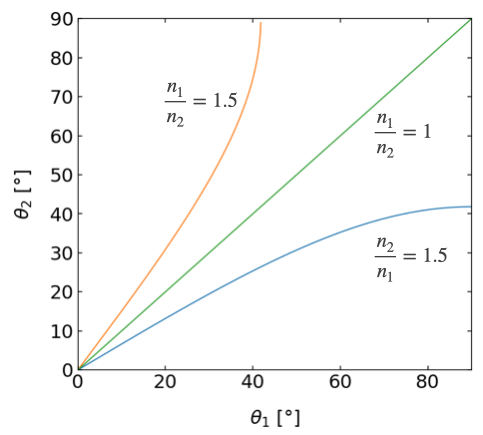

The plot below shows this result in three plots with varying incident angle and two different refractive index combinations (glass/air, ait/glass).

|

|---|

Fig.: Snells law for different combinations of refractive indices. |

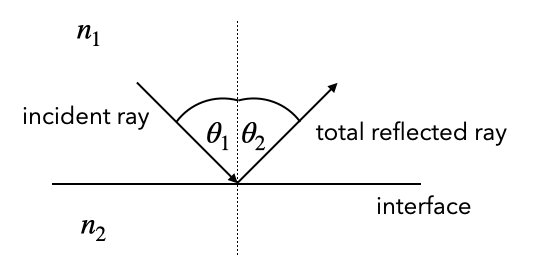

Total Internal Reflection¶

The above diagram reveals a special case occurring when

Let’s first formalize this. Using the Snell’s law. For

for the critical angle

|

|---|

Fig.: Total internal reflection |

Total Internal Reflection

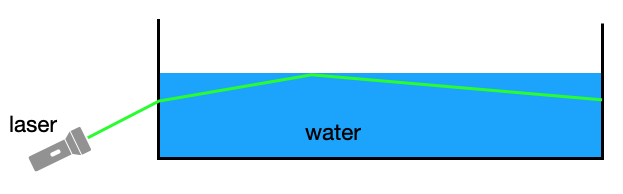

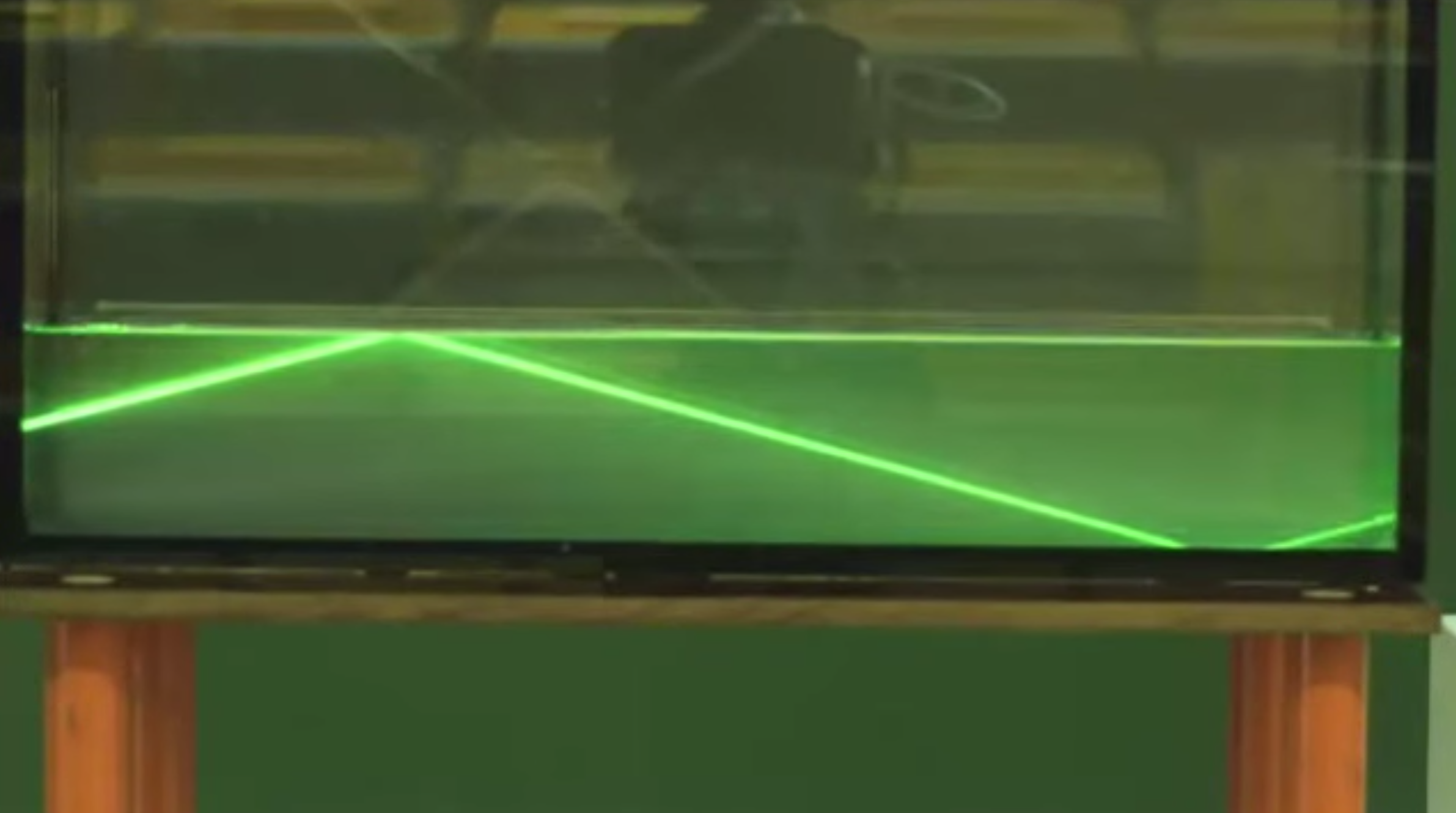

Total internal reflection occurs when light is passing from higher refractive index to lower refractive index materials for incidence angle larger than a critical angle

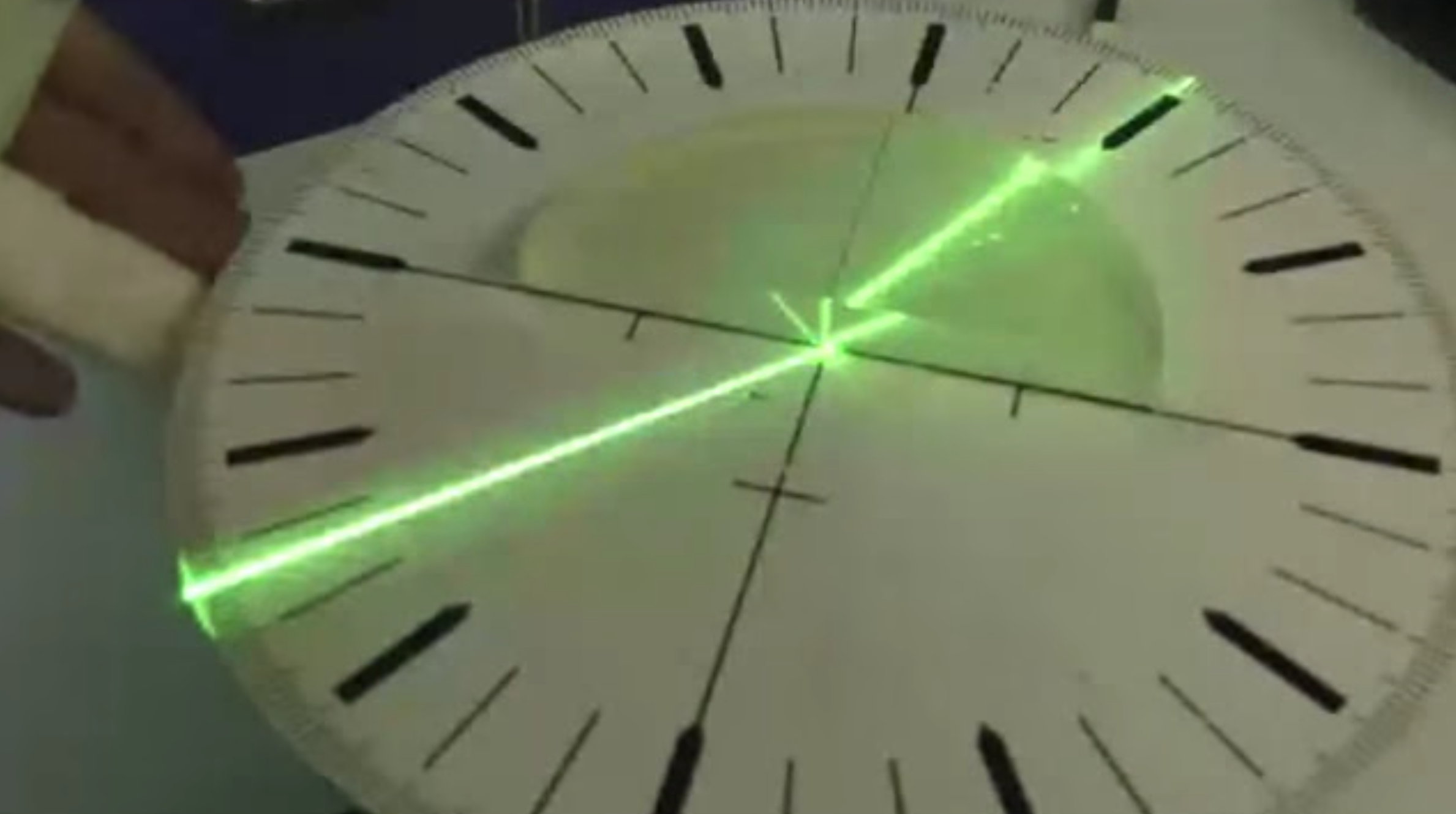

We can demonstrate total internal reflection very easily with a water basin, for example, where we couple in light from a laser from the side.

|

|---|

Fig.: Total internal reflection at a water/air interface. |

But you could try that yourself also in the bath tub diving below the water surface.

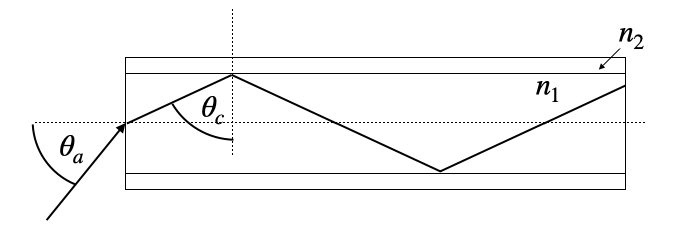

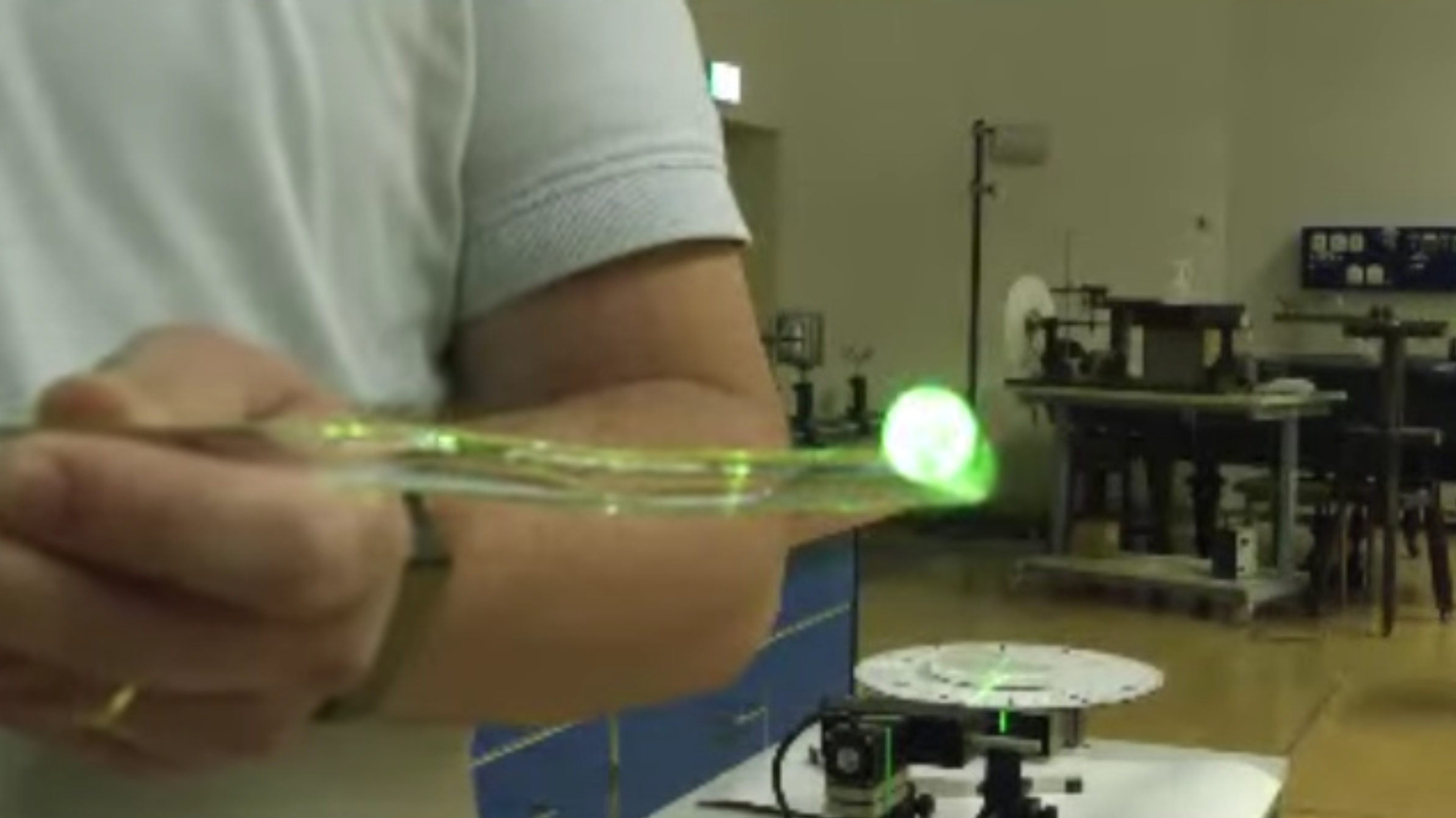

Optical Fiber Total internal reflection is very important for guiding light in telecommunications, for example. There, glass wires with a diameter from a few to several 100 µm are used to transport light. The glass wire with a central core of refractive index

|

|---|

Fig.: Total internal reflection in an optical fiber and a glass rod. |

The angle

Using typical values of the refractive indices